Introduction

Mickaboo Companion Bird Rescue was founded in 1996 to provide care, rehabilitation and permanent homes for companion parrots in need. While its mission is rooted in compassion, systemic issues within the organization have compromised its ability to serve the birds in its care. Many parrots remain in foster homes for years without access to preventive care, while adoption screening, training and post-adoption support are minimal, leading to behavioral problems, frequent returns and chronic overcrowding.

Serious conflicts of interest further undermine the organization’s integrity. A veterinarian without specialist credentials receives a disproportionate share of Mickaboo’s funding (76%) and maintains close personal relationships with board members. This dynamic has resulted in questionable, prolonged treatments with poor outcomes and unsustainable costs. Preventive care is routinely neglected, and medical decisions often rely on personal opinion rather than current, peer-reviewed veterinary science. Additionally, leadership has repeatedly prioritized internal relationships over animal welfare, marginalizing volunteers who raise concerns and failing to implement meaningful reforms.

Mickaboo’s focus on wild conures illustrates further mission drift. Although these birds account for only 6.5% of those in care, they consume nearly 30% of total care costs. A small subset of severely disabled wild conures alone has driven nearly 15% of total expenses, diverting resources that could be better spent on behavioral training and preventive care away from companion parrots. The organization lacks the expertise and infrastructure of a wildlife rescue, and many wild conures are permanently housed in private homes or veterinary clinics, despite ethical concerns regarding their long-term captivity and quality of life.

A related issue is Mickaboo’s reliance on prolonged hospitalization at vet clinic For The Birds (FTB), where birds often remain for months or years under questionable circumstances. At present, approximately 30 birds are boarded or hospitalized at FTB, with most having stayed for longer than a month and some for multiple years. Cases like Muriel, an African grey parrot who has remained at FTB for over eleven years, and Boomer, a Green-wing Macaw whose care costs have exceeded $105,000 in five years, illustrate a troubling pattern. Despite significant investment in their care, both birds’ cases reveal a lack of targeted behavioral intervention, clear treatment goals or consideration of more appropriate long-term solutions. Long-term boarding at a local boarding facility compounds the problem.

Mickaboo faces significant internal challenges rooted in dysfunctional leadership, operational inefficiencies and a poorly managed educational framework. Leadership is widely viewed as inconsistent, overly centralized and resistant to feedback. Key decisions are frequently overridden by a small number of individuals, who have a history of undermining species coordinators and making unilateral calls on adoption and foster applications. This has eroded trust amongst volunteers and created a climate of unpredictability and favoritism. The lack of accountability and transparency contributes to high volunteer turnover, low morale and a culture that discourages initiative.

Operationally, the organization struggles with outdated infrastructure and inefficient systems. Its core platforms—used for communication, record-keeping and case management—are often slow, unreliable or confusing to navigate, delaying urgent tasks and frustrating volunteers. Basic processes like onboarding, training and internal coordination remain underdeveloped or inconsistently applied. The educational structure, intended to prepare fosters and adopters, suffers from outdated or incomplete content, minimal support from leadership and a failure to incorporate current science. Despite volunteer-led efforts to modernize training materials, leadership delays approval or fixates on minor stylistic issues, stalling progress and leaving new volunteers and adopters underprepared for the complex care many birds require.

These practices reflect a misallocation of resources and an absence of sound operational oversight. Without meaningful structural reform and renewed focus on its original mission, Mickaboo will continue to fail the very birds it was created to protect.

Finances

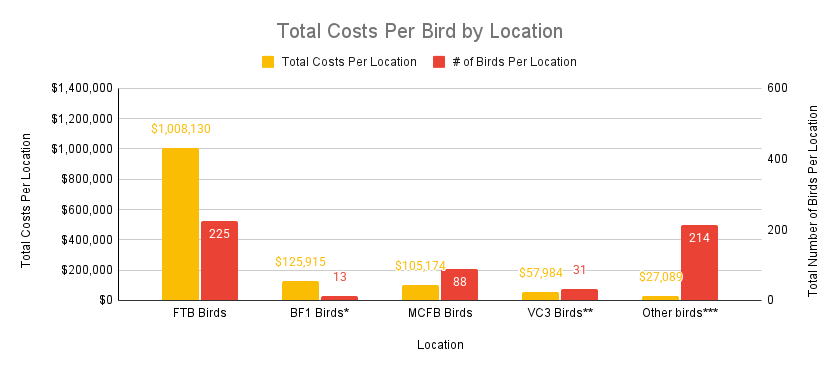

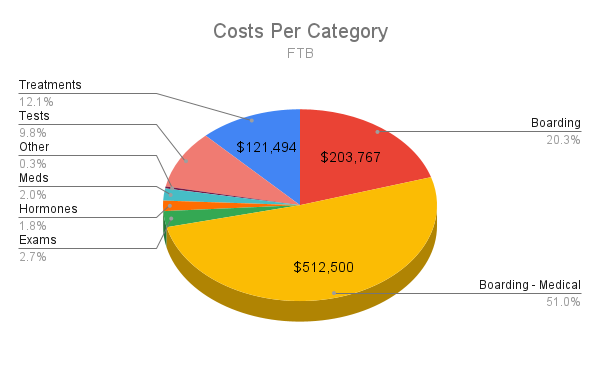

During the 24-month period from September 2022 to September 2024, Mickaboo spent over $1.3 million on veterinary expenses for approximately 570 birds. However, these costs were highly concentrated at two facilities. For the Birds (FTB) alone accounted for 76% of all expenditures while serving just 39.5% of the birds, with an average cost per bird of $4,481. Boarding Facility One (BF1) also showed disproportionate spending, consuming 9.5% of funds for only 2.3% of birds, with average costs exceeding $9,600 per bird. In contrast, clinics like the Medical Center for Birds (MCFB) and Vet Clinic Three (VC3) served more birds for a fraction of the cost, averaging about $1,200 and $935 per bird respectively.

The majority of Mickaboo’s spending went toward boarding services, both medical and non-medical. At FTB alone, 72% of costs were for boarding, with long-term stays common. A small number of birds drove a large portion of expenses—23 birds (4% of the total population) accounted for 50% of FTB’s total costs.

While this analysis aimed to assess service distribution and cost-effectiveness, it was limited by incomplete records, vague service descriptions and inconsistent data across platforms. Despite these limitations, the data indicates a strong imbalance in financial priorities, with the bulk of funding going to costly and extended stays at select facilities while many other birds receive minimal or no care.

Misuse of Funds and Conflicts of Interest

Mickaboo has increasingly diverted resources toward off-mission activities,1Mickaboo’s Mission Statement and Organizational Structure most notably the care of wild conures, despite not being a licensed wildlife rescue. These birds now account for approximately 30% of the organization’s total bird care costs, even though they make up only 6.5% of the foster population. A handful of these conures, many of whom are severely disabled and unlikely to be adoptable or live without substantial medical intervention, have each cost tens of thousands of dollars. While some leadership figures, including the founder, argue these birds deserve continued care, others raise ethical concerns about the quality of life. The lack of expert oversight in determining which birds can adapt to life in captivity further underscores Mickaboo’s unpreparedness to manage wildlife rehabilitation.

Simultaneously, Mickaboo’s heavy reliance on long-term boarding at a single veterinary clinic and one boarding facility contradicts its public claim of operating a foster-based model. Over 65% of Mickaboo’s bird care costs during the two-year focus period were spent on medical and non-medical boarding at FTB, which houses birds for months or even years. This practice undermines the organization’s mission to prioritize quality of life through home-based care and creates significant disparities in the allocation of care. Many companion birds are denied preventive care due to cost, while a small number receive extensive and expensive treatment.

These problems are exacerbated by entrenched conflicts of interest. FTB, operated by Dr. Fern Van Sant—who lacks board certification in avian medicine but maintains close personal ties to Mickaboo leadership—receives the majority of Mickaboo’s referrals and has been paid millions of dollars over the years. Leadership consistently promotes her services while dismissing or discrediting board-certification,2Call for Independent Auditing despite Mickaboo’s own policy that certified care should be used “wherever possible.” Volunteers who raise concerns are often silenced or marginalized, fostering a culture of defensiveness and suppressing scrutiny.

More broadly, the organization resists calls for clear vetting standards, external oversight or accountability regarding its network of veterinarians. While only a few of Mickaboo’s “approved” clinics employ board-certified avian specialists, volunteers questioning this inconsistency are accused of creating division.3Slack Discussion about Vets This has created a chilling effect around open discussion of best practices in avian care. Ultimately, Mickaboo’s misplaced priorities, lack of credential-based standards, and persistent resistance to criticism raise serious ethical concerns and threaten the credibility and effectiveness of the organization’s mission.

Care and Welfare Concerns

Mickaboo is currently grappling with serious care-related challenges driven by overcrowding, inconsistent policies, lack of preventive veterinary care and questionable treatment practices. The organization routinely accepts birds without securing foster homes, including birds not in urgent need. This has led to overcrowding in private homes and facilities such as FTB and Boarding Facility One, where birds are often kept in large numbers under inadequate conditions. Overcrowding undermines socialization, increases disease risk and creates environments that compromise welfare.

Extended foster periods are another systemic problem. Nearly two-thirds of Mickaboo’s birds have been in care for over two years, with some birds remaining for a decade or longer. Rather than focusing on long-term placements, leadership often prioritizes new intakes. Some fosters, unaware of the long-term commitment and unable to move what they thought would be short-term placements, have threatened to surrender birds to shelters. In other cases, fosters retain birds indefinitely so that Mickaboo continues to cover their vet costs, further draining resources.

Preventive veterinary care, despite being promoted in Mickaboo’s materials, is inconsistently provided. Fosters are often denied routine wellness exams,4Mickaboo’s Foster Agreement states preventive care is not provided. even when funded through donations meant to be allocated specifically to them. The approval process for veterinary care is slow and unclear, contributing to delayed treatment and poor outcomes. Meanwhile, a small group of birds at FTB receive excessive testing and treatments, contributing to financial imbalance and raising questions about necessity and oversight.

Concerns have also been raised about veterinary protocols at FTB recommended by Dr. Van Sant.5Discharge Report Showing care recommendations with questionable protocols highlighted. These include the routine use of hormone treatments like Lupron6Tammy recommending Lupron just for the heck of it and Deslorelin (an FDA-indexed drug not approved for birds), discouragement of enrichment items like chewable and shreddable toys, and questionable dietary recommendations. These practices often contradict current avian veterinary literature and behavioral science, resulting in over-medicalization and inadequate behavioral support.

Behavioral training and follow-up are poorly supported. Many fosters and adopters are insufficiently trained to manage complex species, resulting in high return rates and worsening behaviors. Mickaboo frequently favors pharmacologic interventions over evidence-based behavioral support, despite the known benefits of proactive training and environmental management. Birds labeled as “aggressive” or “damaged” are often boarded indefinitely at FTB rather than being given targeted behavioral help or placement opportunities.

The pattern of long-term hospitalization is particularly troubling. Some birds have been held at FTB for years—one for over a decade—with minimal evidence of ongoing rehabilitation. Case studies, including African Greys Max and Evie, show dramatic improvement after being removed from FTB and placed in supportive, enriching environments. These examples highlight the need for reevaluation of FTB’s role and practices in bird care and raise serious concerns about labeling, treatment standards and long-term outcomes.

Addressing these systemic issues—especially overcrowding, excessive boarding, lack of preventive care and overreliance on questionable medical treatments—is essential to restoring Mickaboo’s alignment with its mission to promote the welfare and placement of companion birds.

Leadership and Accountability Failures

Mickaboo has faced a prolonged leadership vacuum, with no permanent CEO since 2022 and no acting CEO/COO since October 2024. Despite internal acknowledgment of the need for experienced professional leadership, the board has failed to recruit replacements or implement a strategic hiring plan. Instead, day-to-day leadership has defaulted to a small group of long-time officers who lack operational familiarity, exacerbating burdens on already overextended volunteers. This absence of clear structure, planning and direction has left the organization in a state of ongoing instability.

The board itself has proven apathetic and ineffective. Many long-standing problems—some dating back over a decade—remain unaddressed, including the strain of managing both domestic parrots and wild conures. Meeting minutes are inconsistently archived, communications have slowed or ceased altogether, and volunteers are left without insight into decisions that affect the organization’s direction. This lack of transparency deepens internal disconnects and undermines trust.

Operationally, record keeping is poor. Key data—such as diagnostic results, invoices, and surrender or adoption fees—are missing or incomplete in Mickaboo’s system, hindering oversight and informed decision-making. Financial transparency is equally lacking. Data is kept on personal computers, with no organizational oversight or shared access. Donors are not informed that contributions may be used for off-mission expenditures, including long-term boarding and wild conure care. Even when donors give funds for specific birds, the money is absorbed into the general fund with no guarantees for how or where it’s used.

Mickaboo recently introduced a whistleblower policy—seemingly in response to nonprofit watchdog standards—but the designated contact holds a long-term leadership position, raising concerns about impartiality. Given the organization’s pattern of discouraging internal criticism and consolidating control amongst a few individuals, this policy risks becoming a symbolic gesture rather than a genuine tool for reform. Without structural changes, transparency, and external accountability, Mickaboo’s internal dysfunction is likely to persist.

Operational Deficiencies

Mickaboo’s internal operations are marked by dysfunction, micromanagement and a lack of accountability, resulting in high volunteer turnover and widespread burnout. Leadership behavior—particularly from former COO Sarah Lemarie and long-time board president Tammy Azzaro—has been characterized by inconsistent enforcement of policies, favoritism and a failure to delegate or support volunteers. Volunteers report feeling sidelined, dismissed or micromanaged, which has caused many to disengage or leave the organization entirely.

Decision-making is often arbitrary. Species coordinators are nominally empowered but regularly overruled without explanation. Some applicants and fosters face undue scrutiny or delays, while others bypass key steps entirely, often due to personal relationships with leadership. This inconsistency erodes trust and leads to poor placement decisions that put birds at risk. Leadership also fails to uphold the same standards it demands of others—housing birds in overcrowded or noncompliant conditions that would not pass Mickaboo’s own home visit guidelines.

The organization also struggles with onboarding and volunteer support. New volunteers receive little training and are often excluded from decision-making, while long-time members dominate operations through informal power structures. Without clear expectations or shared responsibility, essential work is left unfinished and operational gaps persist.

Administrative processes are slow and inefficient. Applicants may wait months for responses, and communication is often poor or absent. Leadership avoids conflict and refuses to replace inactive volunteers, creating bottlenecks across the organization. Key roles—like fundraising—are held by individuals with limited experience, who resist professional support, limiting Mickaboo’s ability to grow and sustain its mission.

Overall, Mickaboo’s internal culture—defined by reactive leadership, arbitrary enforcement, and resistance to change—prevents it from functioning effectively or fulfilling its potential as a rescue organization.

Education and Communication Challenges

Mickaboo faces serious challenges in its educational and communication systems, stemming from outdated materials, poor volunteer training and neglected infrastructure. The Basic Bird Care Class—required for prospective adopters—is largely ineffective, riddled with inaccuracies, and delivered in an overwhelming format. Participants frequently leave unprepared, often failing to grasp basic husbandry standards. Feedback highlights difficulty understanding instructors, broken follow-up resources, and the inclusion of advanced material inappropriate for beginners.

Attempts to modernize the class—such as developing a self-paced online version—have stalled for years. Although a group of volunteers successfully built a new version on the LearnWorlds platform7LearnWorlds Basic Bird Care Class and received positive internal feedback, leadership has delayed approval, focusing on minor stylistic critiques instead of supporting launch. This has left the live class as the only option, offered just once a month and inaccessible for some.

Volunteer training is similarly lacking. There is no structured onboarding process, centralized resource hub, or technical guidance, leaving volunteers to self-navigate complex systems. While some have created training materials on their own, these tools are unofficial and unsupported—funded out of pocket and often ignored by leadership.

Mickaboo’s website suffers from poor design, outdated content and inconsistent quality.8Mickaboo.org Key information is difficult to find, and until recently, pages included unrelated comics that triggered a copyright complaint. There is no content governance or approval process, and internal resistance has blocked proposed improvements. The site requires a full redesign, a formalized content workflow, and better alignment with modern web and accessibility standards.

Social media presence is weak and formulaic, largely handled by two overstretched individuals with no digital media expertise. As with other areas, central control has driven away skilled volunteers who were willing to help but never given the opportunity. This limits Mickaboo’s ability to engage the public or grow its reach.

Finally, critical infrastructure remains outdated and unstable. The server hosting ASM and other tools is over a decade old, with recurring failures and slow performance. Although leadership acknowledged the need for a replacement and allocated funds, progress has stalled. A temporary $500 upgrade to an old backup server delays the inevitable and reflects a broader unwillingness to invest in sustainable solutions.9Server Patch

Conclusion

Mickaboo’s core mission—to rescue, rehabilitate, and rehome companion birds—is being steadily undermined by systemic dysfunction and persistent leadership failures. Inconsistent adoption practices, volunteer attrition, misuse of donor funds, lack of preventive and behavioral care, and a refusal to implement necessary reforms have created an organization that is increasingly reactive, opaque and misaligned with best practices. Critical decisions are often made without input from qualified professionals, and key initiatives are delayed or blocked altogether. While volunteers continue to give generously of their time and resources, the organization’s internal structure and leadership approach routinely sabotage those efforts—leaving the birds without the level of care they need and deserve.

If Mickaboo is to uphold its responsibilities to both donors and the animals it serves, immediate structural reform is essential. This includes implementing transparent financial practices, modernizing volunteer training, investing in preventive and behavioral care, and seeking guidance from credentialed specialists. Without meaningful change, Mickaboo risks failing in its fundamental mission and betraying the trust of the community, its volunteers, and most importantly, the vulnerable birds in its care.

Given the depth and persistence of these systemic failures, it is no longer sufficient to hope for incremental change from within. The current board has repeatedly demonstrated an unwillingness or inability to lead with transparency, accountability or urgency. For the sake of the organization’s future and the well-being of the birds in its care, we urge the full board to step down and make way for a restructured leadership team—one committed to ethical governance, professional expertise and true mission alignment. Mickaboo’s continued existence depends on it.