Detailed Report

Parrots are amongst the most complex and misunderstood pets. While their intelligence, beauty and social nature make them appealing companions, they are not domesticated animals and require specialized care and long-term commitment. Public perception of parrot ownership is often shaped by social media and pet store marketing, which highlight the entertaining and affectionate aspects of parrots while overlooking the significant challenges of meeting their physical, emotional and behavioral needs. Parrots are loud, messy, and possess powerful beaks. Building a positive relationship with them depends on treating them with respect and engaging with them according to their natural communication style. What is often a mismatch between expectation and reality contributes to high rates of surrender, neglect and rehoming.

Parrots are often surrendered due to owner lifestyle changes such as family growth, household shifts or, simply, disinterest. Their long lifespans mean many outlive their caregivers. Others have suffered neglect, mistreatment or behavioral challenges, and some come from hoarding situations. In severe cases, parrots are relegated to garages, basements or isolated rooms, deprived of interaction or stimulation. Many are confined to cages that are too small or covered in waste. Some have not been allowed out of their cages for years, have lived without toys or have never even been given a name. Prolonged isolation often leads to extreme fear and distress, causing some birds to thrash, injure themselves, or display other signs of psychological trauma.

As highly intelligent, social animals, parrots require enrichment, foraging opportunities, time outside their enclosures and regular interaction with human companions. When these needs are unmet, they may develop serious behavioral issues, including feather plucking, excessive vocalization and aggression, which can further contribute to their surrender or neglect.

However, with proper care, attention and training, many of these birds can be rehabilitated, allowing them to live healthier, happier lives. Mickaboo is a companion parrot rescue organization dedicated to addressing and mitigating the challenges faced by parrots in need. Founded in 1996 in Northern California, Mickaboo is a registered 501(c)3 nonprofit organization (FEIN 94-3286344). Most of our volunteers and foster birds live in the San Francisco Bay Area and Sacramento Valley. As stated on our website, our goals are:

- To ensure that birds in our care will have a safe, loving environment for life.

- To educate bird owners on the most current standard of care, so that the medical, emotional and dietary needs of their birds will be met.

At Mickaboo, our underlying principle is that “Every Bird Gets An Equal Chance.” Once a bird is in our care, we provide all the medical and supportive care that s/he requires. We do not “triage” birds or spend more money on large species than small. We only euthanize a bird when s/he is suffering without the possibility of recovery. We provide hospice care for terminally ill birds who are not suffering.1See Mickaboo’s “Organizational Structure” document. It’s from 2009. We think this is the most up-to-date copy, but it is unclear, because Mickaboo’s lacck of transparency means corporate documents are not easily accessible

Mickaboo aims to carry out its mission through several key initiatives:

- Education: Educating current and potential parrot caregivers about proper parrot care, helping to prevent future surrenders and improving the lives of companion birds.

- Foster Care: Placing birds in temporary foster homes, ensuring they receive care and attention until they can be adopted into loving, permanent homes.

- Adoption Vetting: Carefully screening and vetting potential adopters to ensure each bird is placed in a safe and nurturing environment.

- Medical Care: Providing essential medical treatment to foster birds, helping them regain health and well-being.

- Training: Working with foster birds to address behavioral issues and prepare them for successful integration into their new homes.

Mickaboo makes a promise to bird owners: should they pass away or become unable to care for their birds, we will find similarly loving homes to honor their wishes.

However, in a significant number of cases, Mickaboo is falling short of its mission and, in some instances, unintentionally contributing to the challenges it aims to resolve:

- Many birds remain in foster care for years, while others are passed from home to home.

- For those birds in foster homes, no preventive vet care is provided.

- The lack of sufficient foster homes, combined with excessive bird intake, has resulted in severe overcrowding situations within the organization itself, as well as costly boarding at a commercial boarding facility and a vet’s office.

- Education of potential adopters is limited to one class, with some material that is questionable, at best.

- Training and follow up are virtually non-existent, contributing to high bird return rates, often due to behavioral reasons.

- Adoption vetting falls short, and birds are placed with inexperienced individuals or those who neglect or mistreat them, creating or exacerbating behavioral problems.

Mickaboo, though founded and operated by well-meaning individuals, faces significant structural and operational issues that undermine its mission. While the organization seeks to provide safe and loving homes for companion parrots, the following challenges illustrate how systemic mismanagement and conflicting priorities hinder this goal:

Misplaced Priorities, Conflicts of Interest and Ethical Concerns

- Misplaced Priorities: Despite not being a wildlife rescue or sanctuary, Mickaboo has devoted substantial resources to rescuing wild conures and the long-term boarding of birds. These practices raise concerns about mission drift and inefficient use of organizational funds.

- Conflicts of Interest: Serious conflicts of interest exist within the board, particularly involving personal relationships with Dr. Fern Van Sant of For the Birds (FTB), who receives the majority (76%) of Mickaboo’s veterinary funding.

- Co-Founder Interference: Co-founder Tammy Azzaro, a veterinary technician, frequently makes medical decisions that may contradict the recommendations of experienced avian veterinarians.

- Resistance to Criticism: Volunteers who raise concerns about these issues are often ignored or ostracized as the board appears to prioritize protecting Dr. Van Sant over addressing valid criticisms.

Care Concerns

- Consistently exceeding our intake and humane capacity: Because of the large number of birds in need, we often exceed our intake capacity, leading to overcrowding.

- Extended Foster Periods: Many foster birds have been in care for years, and there is a high rate of foster home turnover and returned adopted birds.

- Lack of Preventive Care: Birds in long term foster care are not receiving the most basic preventive care that we demand from adopters, even if donors have explicitly contributed funds for a specific bird.

- Questionable Veterinary Practices: While some birds receive no care at all, others undergo excessive and potentially unnecessary treatments, including questionable procedures and prolonged hospitalization. FTB is the primary location where this occurs,

- Lack of Behavioral Training, Inadequate Vetting and Follow Up: Mickaboo’s vetting process for fosters and adopters is too often insufficient, leading to placements with individuals who misrepresent their circumstances, fail to apply training, or exhibit overlooked warning signs. Additionally, coordinators often neglect to review prior records, resulting in repeated issues when placing additional birds with the same individuals. Although Mickaboo claims to work with foster birds to address behavioral issues, this rarely takes place.

- Extended Hospitalization: Many birds have been hospitalized at For the Birds for months or years, at significant expense to the organization.

- Neglect of Challenging Birds: Birds labeled as “damaged” or “aggressive” are often transferred to FTB, where they are effectively abandoned and forgotten, receiving little to no effort toward focused efforts at rehabilitation or, ultimately, placement. These birds remain where they are, without an exit strategy, at significant costs to Mickaboo.

Leadership, Accountability and Cultural Failures

- Leadership Void: Mickaboo has not had a permanent CEO since Michelle Yesney quit the position in 2022. Its acting CEO/COO quit in October 2024 and has yet to be replaced. Tammy, the board’s nominal president, has not once addressed the volunteers or other stakeholders in a leadership capacity since the interim CEO stepped down.

- Apathetic Board: Internal communications reveal that while board members are fully aware of the organization’s issues, they consistently fail to take action to address them.

- Lack of Transparency: Poor record-keeping, conflicts of interest and exclusion of volunteers from decision-making undermine accountability, mislead donors, and reflect a broader culture of organizational dysfunction.

- Ineffective Whistleblower Policy: While Mickaboo recently implemented a whistleblower policy, it is largely ineffective.

Operational Definciencies

- Ineffective Leadership: The organization’s top leadership roles have been occupied by individuals who are difficult to work with, which has contributed to a hostile and unproductive work environment.

- Broken Organizational Culture: Mickaboo’s internal culture, which applicants and volunteers are expected to adhere to, is dysfunctional, inconsistent and counterproductive.

- Volunteer Turnover: Low morale and high turnover amongst volunteers are common, stemming from poor leadership, lack of support, and frustration with systemic issues.

- Slow and Inefficient Processes: Mickaboo’s operations are plagued by leadership bottlenecks, lack of accountability, and a culture that resists delegation and constructive feedback, resulting in chronic delays, underutilized volunteers, and stagnation that prevents the organization from fulfilling its mission effectively.

Education and Communication Challenges

- Outdated and Inaccurate Materials: Some of the educational materials provided to fosters and adopters are outdated, ineffective or, in some cases, harmful.

- Poor Volunteer Training: Coordinators and administrators are not adequately familiarized with Mickaboo’s guidelines or educational materials, leading to inconsistent decision-making.

- Outdated Website and Poor Social Media Presence: The organization’s website faces significant challenges in design, content management and oversight, leading to an overall lack of professionalism and functionality.

- Neglect of Infrastructure: While Mickaboo takes pride in allocating funds primarily toward bird care, its reliance on outdated infrastructure, such as the website and server, creates unnecessary challenges for volunteers and detracts from the organization’s professional image.

This list highlights the urgent need for structural reform, better leadership, updated training and a renewed focus on the core mission of rescuing and rehabilitating companion parrots. Addressing these issues is critical to ensuring Mickaboo fulfills its responsibilities to the birds and the community.

Finances

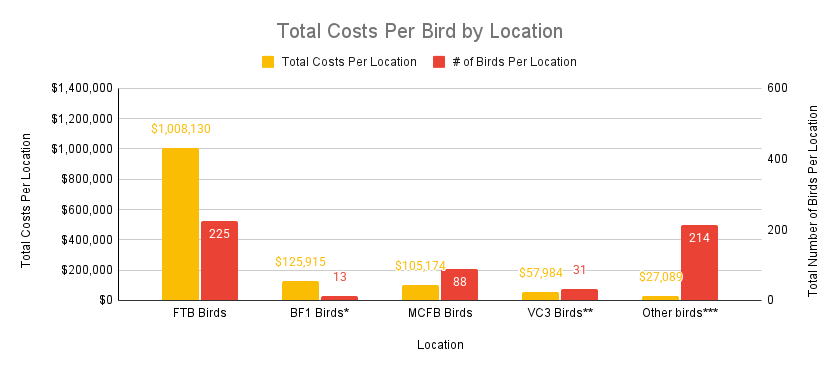

Before we can begin any discussion of Mickaboo’s internal issues, we need to examine the most tangible evidence of it: our finances. To that end, we have undertaken an audit of what intakes and expenditures we could find. Approximately 75% of our yearly expenses are concentrated at For the Birds (FTB). Another 10% goes to Boarding Facility One (BF1), 8% to the Medical Center for Birds (MCFB) and 4% to Vet Clinic Three (VC3).2We have redacted the names of certain parties and organizations. The remaining amount is unclassified.

Methodology

For this analysis, we focused on a 24-month period spanning September 1, 2022 to September 1, 2024, as this period contains a complete dataset for FTB and MCFB costs, if not for those from Vet Clinic Three and Boarding Facility One. In the rest of the document, we call this the “focus period.” In a few cases, we examined costs for specific birds beyond this timeframe.

We calculated the total number of birds that came through Mickaboo’s system during this time period based on data in ASM, Mickaboo’s shelter management system.

We have access to a Mickaboo financial spreadsheet that records detailed financial data across several categories, including donations and grants, adoption fees, other income, total income, veterinary and pet care expenses, other bills, operating net income, interest and dividends, gains and losses from investment sales and net income. This data is organized monthly from January 2009 through August 31, 2024. We were able to compare these totals to the amounts spent at For the Birds during the last four years of this period, and found that For the Birds costs consistently averaged 77% of Mickaboo total costs.

Mickaboo receives bi-monthly invoices from For the Birds (FTB), which provide a breakdown of each bird’s treatments, the cost per treatment, total cost per bird and aggregate treatment costs for each half-month period. These invoices3Available upon request are integrated into ASM.

We have a number of invoices from Boarding Facility One (BF1), though these records may be incomplete, as some months appear to be missing. We have extrapolated from the current data and filled in missing costs. (BF1 Spreadsheet)

We have twelve non-sequential months during 2021 and 2022 from VC34VC3 Invoices available on request to interested parties. We will make assumptions based on this data. First, we doubled the 12 month amount to get an approximate 24-month total. We were comfortable doing this because we have found that totals at other facilities do not vary significantly from year to year. However, it is not as easy to extrapolate the total number of birds seen in a 24 month period. Therefore we have left the number of birds treated at 31, which was the number seen during the 12 month period. We have similarly calculated the percentage of total number of Mickaboo birds and the average cost per bird based only on the 12 month period.

Finally, we have obtained copies of all invoices from the Medical Center For Birds (MCFB) for our focus period.5Available upon request to interested parties.

Invoices typically include bird name, species, date of service, description of service and cost of service. We identified eight broad service categories, including Boarding, Medical Boarding, Exams, Hormones, Medication, Other, Tests and Treatments. We classified each itemized service under one of these broad categories. Within each of these categories, specific service descriptions vary between facilities. We have created a list of service descriptions for each of the three vet facilities and indicated overlap.

To facilitate comprehensive analysis, we manually input data from these invoices into a Cost Analysis spreadsheet. This has allowed us to create an overall view of our expenditures and generate sortable documents. Our primary objective is to determine the percentage of Mickaboo’s veterinary expenses incurred at each vet clinic and boarding facility, and to analyze the services provided to the birds.

Limitations

Mickaboo has limited financial transparency, so we have only a partial portion of the entire picture. We feel, however, that based on organization tax returns, it is safe to assume that the Mickaboo Financial Spreadsheet is accurate, and therefore we are relatively confident of our assessment of total yearly costs. Furthermore, the data above describes totals that adhere to the Mickaboo Financial Spreadsheet. Furthermore, as of May 2025, we have also received a bird care expense breakdown from Mickaboo leadership, themselves.

The data in ASM includes very few costs or invoices from any of the other seven or so veterinarians we use, making it impossible to determine exact totals of costs and birds. Once we have subtracted the costs and number of birds from available data, we are left with a category of “other birds.” This is a relatively small amount of money, for a large number of birds. We don’t have a final tally of birds that received vet care, so it is impossible to tell how many did not or how much each bird that received care cost.

We are not veterinarians or medical experts so we cannot know for certain that services at one facility are the same as those at another, just under another name.

Some services are labeled with general terms such as “hospital oral treatment,” leaving the specifics unclear. Additionally, test results, treatment outcomes and necropsy details are rarely recorded in ASM, limiting the scope of our analysis.

Finally, because all data entry was performed manually by volunteers who are not professional auditors or accountants, slight discrepancies may appear in some of the totals presented across various charts and graphs.

Findings6Comparisons of Costs by Location

During the 24-month period from September 1, 2022 to September 1, 2024, approximately 570 birds went through the Mickaboo system. Mickaboo’s total veterinary expenses during this period amounted to $1,324,292, averaging $2,323 per bird, if costs were distributed evenly. However, expenses were significantly concentrated at For the Birds and, to a lesser extent, at Boarding Facility One, where the respective veterinary costs totaled $1,008,130 and $125,915. Of these, 225 birds were seen and/or boarded at For the Birds for medical and non-medical purposes, while 13 were non-medically boarded at Boarding Facility One. MCFB costs totaled $105,174 for 88 birds, and two year costs at VC3 were estimated to be $57,984.

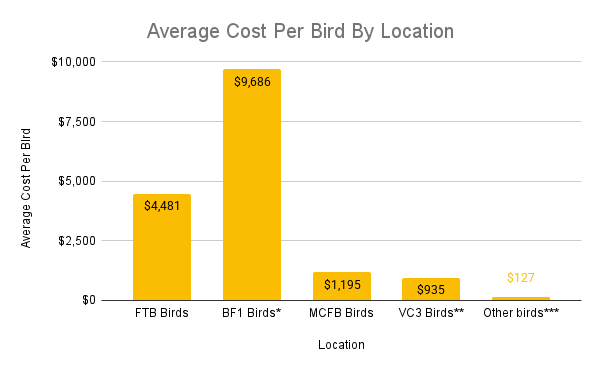

Adjusting for this concentration, the average cost per bird was $4,481 at For the Birds, $9,686 at Boarding Facility One, $1,195 at MCFB, an estimated $935 per bird at VC3, and $127 per all other birds in Mickaboo’s system.

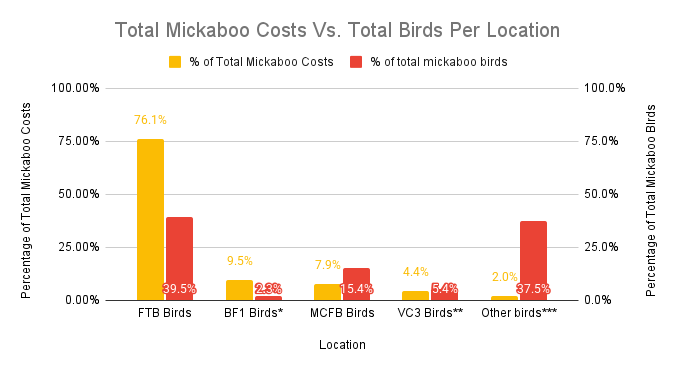

We can assess cost disparities across the four locations by comparing the proportion of total Mickaboo veterinary expenses to the proportion of birds served at each site. Notably, both FTB and BF1 incurred significantly higher percentages of costs relative to the number of birds they served. FTB costs accounted for 76% of total Mickaboo veterinary expenses, while only 39.5% of Mickaboo’s birds were served there. Similarly, BF1 costs represented 9.5% of total expenditures, despite serving just 2.3% of the birds.

At the remaining locations, the percentage of service costs was lower than the percentage of birds served. MCFB costs accounted for 7.9% of total expenses though it served 15.4% of the birds. VC3 costs accounted for 4.4% of expenditures, though it served 5.4% of the birds. Meanwhile, the remaining 37.4% of Mickaboo’s birds, served by Mickaboo’s other vets (or not at all), represented just 2% of total expenses.

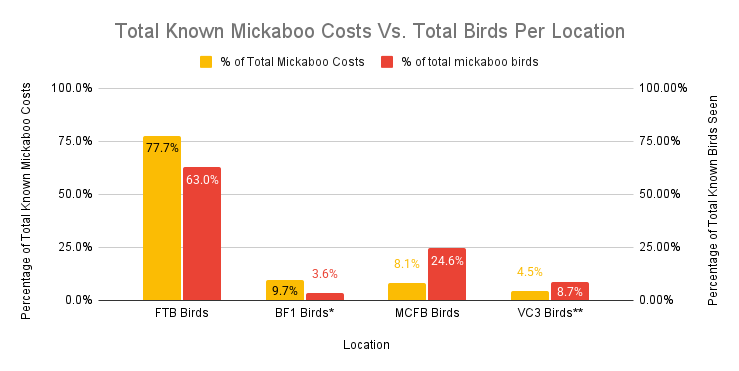

Excluding the “other birds” category and focusing solely on known costs and known served birds, the distribution remains similar. FTB and BF1 show higher percentages of costs relative to the percentage of birds served, while MCFB and VC3 have higher percentages of birds served compared to their share of costs.

For the Birds7FTB Costs Per Bird

Average costs per bird at any veterinary clinic are expected to differ significantly from actual costs, as care expenses can vary widely depending on the severity of illness or injury for each individual. At For the Birds, however, costs were disproportionately apportioned to one particular species—the Wild Conures (WCs), which are often brought in injured or ill from San Francisco and other Bay Area cities. During our focus period, 225 birds were served at FTB, with an overall average cost of $4,481 per bird. However, the average cost per bird differed substantially based on whether the bird was a Wild Conure or a different species. Due to this disparity, we will analyze costs for WCs separately from those for non-WCs.

Of the 225 birds served at FTB, 38 were WCs, and analysis highlights a significant disparity in service costs. The average cost per Wild Conure was $10,891—nearly three times the $3,449 average cost for non-WC birds.

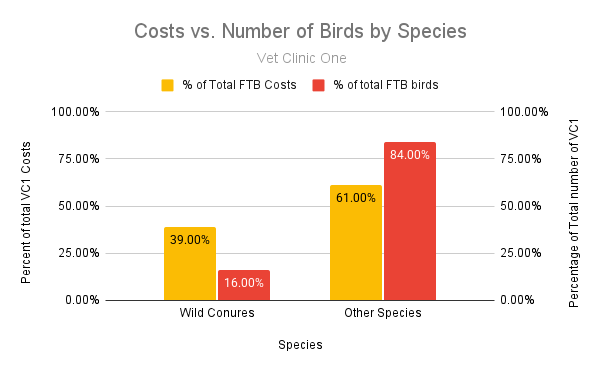

The total costs at FTB amounted to $1,008,130, with Wild Conures accounting for $392,087, or 39% of the clinic’s expenses, despite comprising just 16% of the birds served. In contrast, the remaining 189 non-WC birds represented 84% of the total bird population at FTB but incurred $616,043, or 61% of the costs.

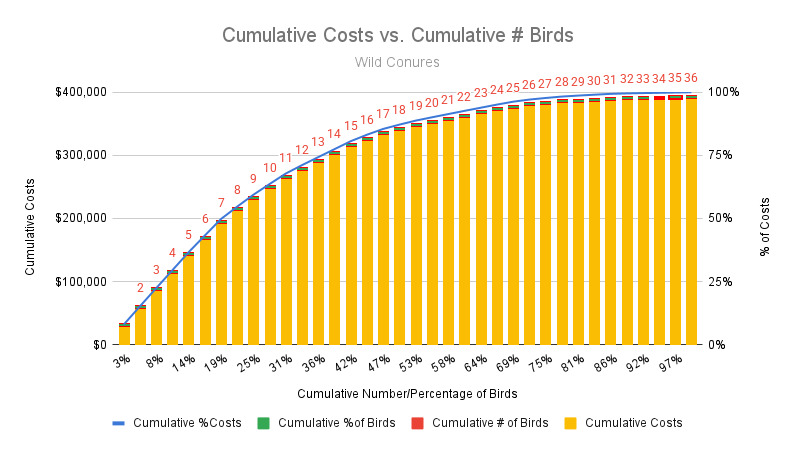

This can be broken down further. Half of the total Wild Conure veterinary costs at For the Birds, amounting to $196,043, were spent on just seven birds, averaging $28,000 each. Furthermore, 90% of Wild Conure costs ($352,878) were incurred by twenty birds, with an average cost of $17,650 per bird.

As would be expected, the individual costs per bird vary widely from the average. The most expensive Wild Conure during the 24-month period analyzed was Poppy, with costs totaling $30,991. Poppy has resided at For the Birds since September 25, 2021, so some of her costs fall outside the focus period. As of this writing, Mickaboo has spent $49,465 on her care. Four other wild conures have surpassed Poppy’s total costs. Bowley, who has been at For the Birds since July 2020, has cost Mickaboo $70,500. Billy, there since June 2018, has incurred similar expenses, exceeding $70,000.

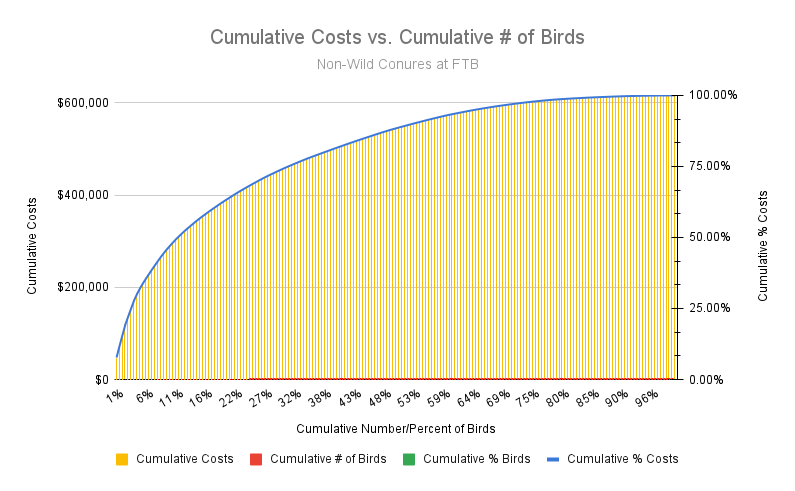

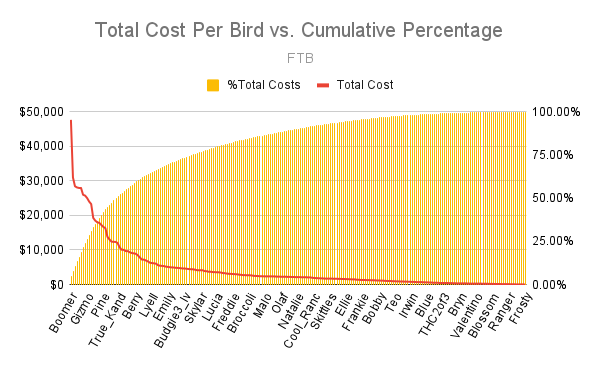

A similar pattern of cost concentration is observed amongst non-Wild Conure species, whose total expenses amount to $616,043. While the average cost per bird is $3,449, expenses are disproportionately skewed toward a small number of individuals. For example, Boomer, a green-winged macaw, accounted for nearly 8% of all non-Wild Conure costs ($47,670) and 5% of total For the Birds costs during the 24-month period, making him the most expensive birds served by For the Birds. Boomer, who has been at For the Birds since July 2, 2020, has accumulated total costs of $105,000 in that time.

Just four birds (macaws Boomer and Gizmo, African greys Evie and Lilly) accounted for nearly 20% of all non-Wild Conure vet costs. All four had been at For the Birds longer than this report’s focus period. Overall, 50% of For the Birds’s total costs–38% of Mickaboo’s total costs–were concentrated on 23 birds, 4% of the total number of birds that went through our system.

Boarding Facility One8BC1 Itemized Costs Per Bird

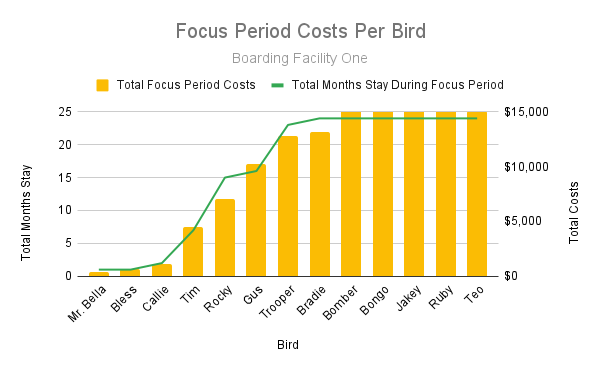

During our 24-month focus period, 13 birds (8 macaws and 5 cockatoos) were boarded at BF1. The cost per bird was determined solely by the length of their stay and species. On the whole, macaws had slightly higher costs than cockatoos. Of these, six birds (Bradie, Bomber, Bongo, Jakey, Ruby and Teo) remained at the facility for the entire focus period.

Eight birds—Mr. Bella, Rocky, Trooper, Bradie, Jakey, Bongo, Bomber and Ruby—are still housed at BF1. Two birds, Teo and Bless, have died, while three—Gus, Tim and Callie—have been adopted. Five new birds have since become residents, bringing the total number of current boarders to 13.

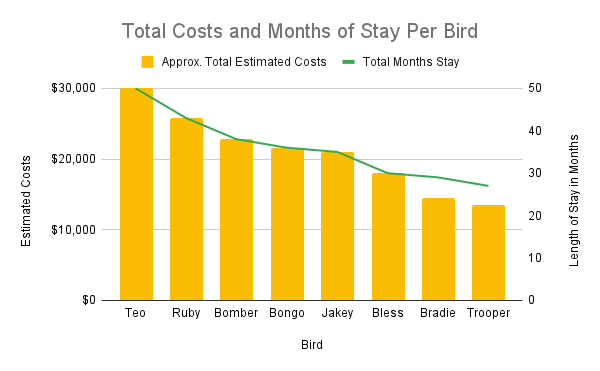

Eight birds have stayed between 27 and 50 months, prompting an analysis of total costs per bird. To estimate these costs, we used conservative average monthly figures: $500 for cockatoos and $600 for macaws. These estimates were based on average monthly costs per species, adjusted downward to account for cost increases since the stay of the first bird, Teo, began. As expected, Teo’s total costs were the highest, amounting to $30,000.

Vet Clinic Three9VC3 Itemized Costs per Bird

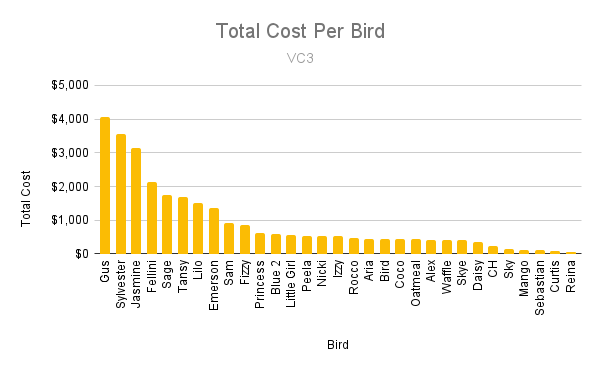

The total expenditure for the twelve non-sequential invoices available from Vet Clinic Three amounts to $28,992, covering 31 individual birds. Even if this figure were doubled, it remains significantly lower than the totals reported by For the Birds and also below the Boarding Facility One totals.

The average cost per bird at Vet Clinic Three was $935. As expected, the data is skewed, with eight birds accounting for 66% of the total costs and an average of $2400 per bird. This distribution is far less pronounced than at For the Birds and does not center on any specific species. The remaining 23 birds, comprising 34% of the total expenditure, had an average cost of $424 each.

Unlike For the Birds, no bird had total costs in the tens-of-thousands, within or outside of the focus period. The highest-cost bird at Vet Clinic Three was Gus, an Amazon parrot, whose care totaled $4,070. Gus is also noted in the For the Birds cost analysis, as his care was transferred there in April 2024. Reina, a conure, had the lowest costs, at $66.

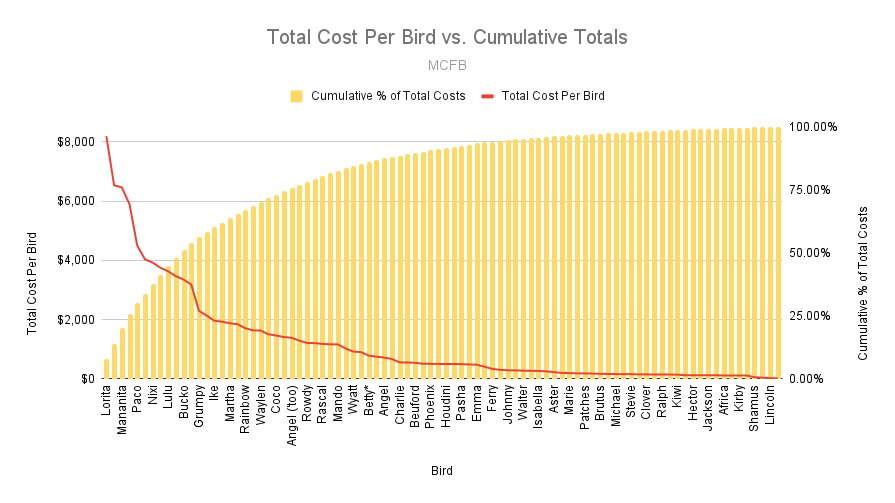

Medical Center For Birds10All MCFB Costs Per Bird

During the focus period, a total of 88 birds were served at MCFB, with cumulative costs amounting to $105,174. This represents an average expenditure of $1,195 per bird. While some birds incurred higher costs than others, there was no discernible pattern linking higher costs to specific species.

The highest-cost case involved Lorita, an Amazon parrot, who required nearly three months of hospitalization in the spring of 2023. This extended length of stay was an outlier and not representative of typical service durations. Her total care costs amounted to $8,200.

In addition to Lorita, 13 birds had service costs ranging from $2,000 to $6,500. Another 18 birds had costs between $1,000 and $2,000, while the remaining 56 birds incurred expenses under $1,000 each.

Cost Categories11Vet Services Per Facility

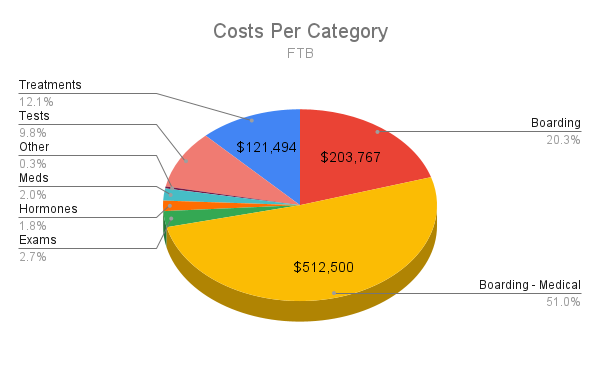

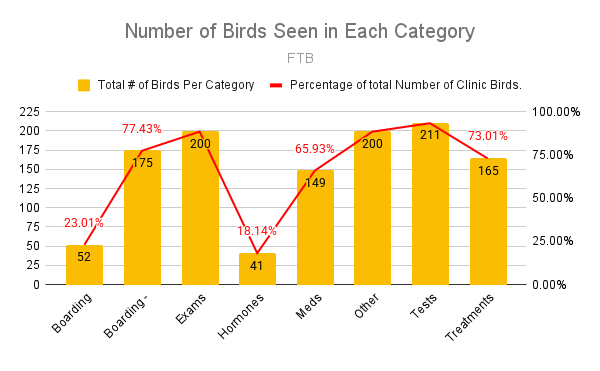

For the Birds12FTB Itemized Costs

The cost analysis for For the Birds underscores substantial expenditure on boarding services. Of the total expenses at For the Birds, 72% ($720,165) was allocated to boarding or medical boarding for 188 birds, including 32 wild conures and 152 birds of other species. Notably, 29 birds utilized both boarding categories, reflecting some overlap.

Boarding expenses are even more significant when considering wild conures alone,13FTB WC Itemized Costs where they account for 90% of the total veterinary costs within the species. The percentage of boarding costs for non-wild conure species, on the other hand, falls to 58%. 14FTB non-WC Itemized Costs

Treatment expenses totaled $121,494, comprising 12% of the overall clinic costs, with 165 birds (73% of all clinic birds) receiving treatments. Diagnostic tests, performed on 211 birds (93% of the total), accounted for $98,206 or 9.8% of total expenditures. Exams, conducted on 200 birds (89%), represented $27,081, or 2.7% of total costs. Hormone treatments, administered to 41 birds (18% of the total), amounted to $17,645, or 2.7% of overall expenses. The remaining $23,800, or approximately 2.4%, was attributed to medications and other services.

The majority of wild conures (86%) received exams, diagnostic tests and other services, while smaller proportions were prescribed medications (36%) or hormone therapy (11%). Collectively, these services accounted for only 10% of the total costs for wild conures. In contrast, treatments and diagnostic tests represented the two most significant cost categories for non-wild conures, amounting to $104,640 (17.2% of total non-wild conure costs) and $86,053 (14%), respectively.

For wild conures, the most common treatments included unspecified inpatient care, inpatient oral therapies, and combined inpatient oral and injectable treatments. Frequently administered medications included Metacam injections (7 birds) and Robenacoxib injections (5 birds). Diagnostic procedures were dominated by gram stains, fecal tests, PDFD/APV/Chlamydia testing, and imaging, while smaller percentages underwent bile acid panels and complete blood counts (CBCs).

Similarly, unspecified inpatient treatments were the most frequently administered to non-wild conures, provided to approximately 38% of this group. Nebulization therapy and saline misting followed, given to 28% and 15%, respectively. Amongst non-wild conure species, gram stains and fecal tests were the most commonly performed diagnostic procedures, administered to about 87% of the population. Vitamin ADE injections were the most frequently used medication, given to 83% of non-wild conures, followed by Robenacoxib and Metacam injections, each administered to 15%.

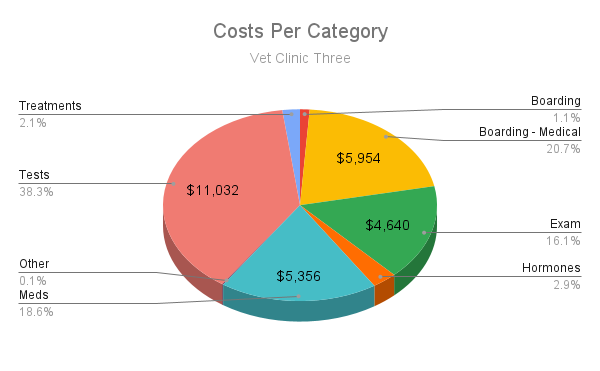

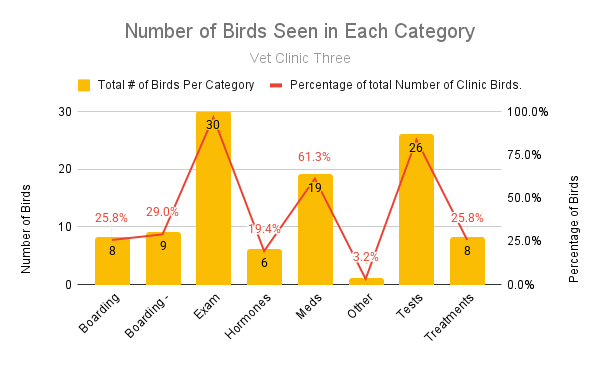

Vet Clinic Three15VC3 Itemized Costs

At Vet Clinic Three, the highest expenditures were for diagnostic tests, totaling $11,032, or 38% of overall costs. Medical boarding followed, accounting for $5,954 (21%), while medications and exams represented $5,356 (19%) and $4,640 (16%), respectively.

Exams were the most frequently performed service, with nearly 100% of birds receiving one. Tests ranked second, performed on 84% of the birds, while 61% received medications and 21% underwent medical boarding. Ciprofloxacin was the most commonly prescribed medication, administered to 10 birds, followed by Meloxicam, given to seven birds. Amongst diagnostic tests, fecal and gram stains were the most frequently conducted, each performed on 24 birds.

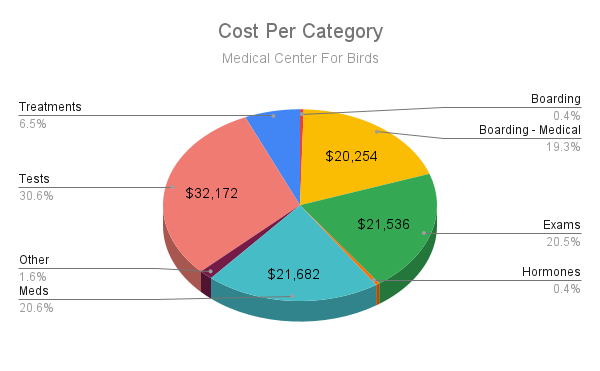

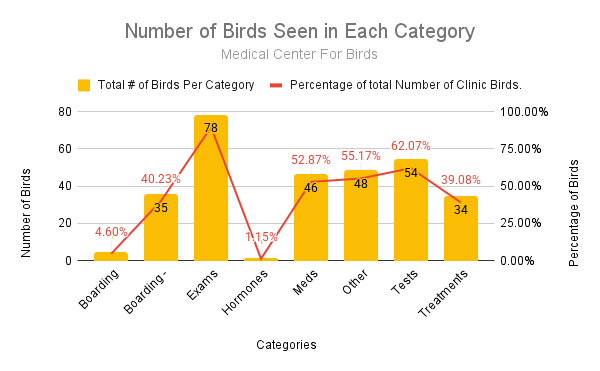

Medical Center For Birds16MCFB Itemized Costs

At MCFB, diagnostic tests constituted the largest expense, totaling $32,172 and accounting for 31% of the clinic’s total costs. Medications, exams and medical boarding each contributed approximately $20,000 to the overall expenses, representing about 20% of the total costs per category.

Exams were the most frequently performed service at the clinic, conducted on 78 birds and representing 90% of all patients. Tests were the second most common, administered to 54 birds (62%), followed by medications, which were provided to 46 birds (53%). Boarding, treatments and other procedures were carried out for 35 birds per category, accounting for approximately 40% of the clinic population.

Amongst birds that underwent testing, hematology was the most common procedure, performed on 33 birds (61% of those tested). This was followed by chemistries, conducted on 28 birds (52%), imaging on 24 birds (44%), and fecal exams on 18 birds (33%).

Meloxicam was the most frequently administered medication, given to 21 birds (24% of those receiving medications). Enalapril was provided to 15 birds (17%), while Tramadol and Isoxsuprine were each administered to 10 birds (11%). Additionally, 20 birds received unspecified “inpatient” medications.

Of the 34 birds that received treatments, procedural sedation was the most common, performed on 22 birds (65%). Fluid therapy followed, provided to 16 birds (47%), and assisted feeding was administered to 12 birds (35%).

Conclusion

Boarding, both medical and non-medical, represents the largest portion of Mickaboo’s bird care expenses. At FTB alone, more than half of all veterinary costs are attributed to boarding. When including expenses from Boarding Facility One (BF1), this figure increases significantly. Over the 24-month period analyzed, $125,915 was spent boarding 13 birds at BF1, bringing the total cost of hospitalized and boarded birds to $846,080—65% of Mickaboo’s total bird care expenditures.

At FTB, 52 birds were boarded for non-medical reasons, a number that rises to 65 birds when including those housed at BF1. The total cost of non-medical boarding across these locations amounts to nearly $300,000, accounting for 22% of Mickaboo’s total bird care costs over the two-year period. Notably, at least 80% of patients at For the Birds experienced some form of boarding, compared to 40% at MCFB and only 22% of birds at Vet Clinic Three. Additionally, extended boarding spanning months or even years is common at For the Birds, whereas it is rarely observed at MCFB or Vet Clinic Three.

Misuse of Funds and Conflicts of Interest

Misplaced Priorities

The Wild Conures

Despite not being a wildlife rescue, Mickaboo has allocated considerable financial and logistical resources to rescuing wild conures without treating them as wildlife or liaising with wildlife regulatory authorities. Mickaboo’s involvement with the wild conures highlights two critical issues:

- Mickaboo lacks the expertise and infrastructure to function as a wildlife rescue.

- The conures consume a disproportionate share of Mickaboo’s resources, and diverting significant funds to wild conure care misrepresents the organization’s mission and misleads donors.

While Mickaboo’s efforts to rescue the wild conures are commendable, they raise significant concerns. As a companion parrot rescue, Mickaboo lacks the specialized expertise required to make humane and ethical decisions about wildlife. While some birds are rehabilitated and released, many are too sick or injured to return to the wild. These unreleasable birds are often kept for months or even years in homes or vet clinics. While some may adapt to life as companion birds, such determinations require expert evaluation, and any homes chosen must prioritize the birds’ individual care and avoid overcrowding.

As discussed above, in our two year focus period, the wild conures in Mickaboo’s care accounted for 30% of all organization expenditures, despite representing just 6.5% of the birds in foster care. Seven of these wild conures alone account for 50% of the total wild conure expenses, meaning these few birds are responsible for nearly 15% of Mickaboo’s total bird care costs. This over-allocation of resources negatively impacts other birds in Mickaboo’s care, many of whom are denied preventive care despite the organization’s stated commitment to such measures. That money would be better spent on behavioral training and enrichment efforts, which could reduce the number of birds returned to Mickaboo for behavior problems.

At the time of this writing, there are approximately fifty-three wild conures in Mickaboo’s care. Fifteen of these are housed at FTB, ten in Dr. Renee Luehman’s home, fifteen in Sarah Laramie’s home, and the others are spread amongst four other foster homes.

Currently, six wild conures require intensive care due to severe disabilities. They cannot perch, and they rely on specialized cages. Their conditions include fecal retention, clostridial infections, and a need for assistance with defecation. Their care involves extensive medical intervention, including anti-inflammatory injections, stool softeners and a specialized diet, along with regular grooming to manage trauma-induced beak deformities. The following three birds provide examples:

Wild Conure Billy, under FTB’s care since June 1, 2018 after being found collapsed on a fire escape, has accrued $70,621 in care costs. Initial testing revealed lead poisoning, prompting chelation therapy, antibiotics, fluids and gavage feeding, with gradual improvement as he began eating independently. Despite ongoing challenges, including his tendency to startle and engage in self-destructive behavior, Dr. Van Sant claims that Billy has shown signs of progress over time. As of this writing, he remains under FTB’s care and continues to face difficulties.

Poppy, under FTB’s care since September 25, 2021, suffered severe spinal trauma, resulting in multiple fractures and little to no leg function. Her care has incurred more than $49,645 in costs and includes pain management, antibiotics, wound care and supportive medications like diazepam and butorphanol, which have helped her remain calm and improved her appetite. While her injuries are complex, and she has poor vascular tone, a bowed femur and a displaced knee, Dr. Van Sant believes ongoing care and potential physical therapy may provide “further insights” into her recovery. Poppy’s long-term prognosis remains uncertain, though again, Dr. Van Sant is “cautiously optimistic” about her potential for improvement.

Jerome, cared for at FTB from July 2018 until his passing in February 2024, incurred $49,891 in care costs. Upon intake, he displayed severe symptoms, including a head tilt, lethargy and gastrointestinal issues, which later revealed bleeding, elevated metal levels and other complications. Despite extensive care and cautious optimism by Dr. Van Sant, his health steadily declined, and in February 2024, a large coelomic mass was discovered. Euthanasia was authorized as the mass was untreatable, marking the end of his prolonged battle with multiple health issues.

Though the board has known for a long time that this is not sustainable,17 Board Meeting Transcript from 9/5/24, Email thread from March 2024 Mickaboo’s co-founder and president, Tammy Azzaro, argues that these birds show resilience and deserve continued care. Similarly, former CEO Michelle Yesney appears to conflate an ill or injured bird’s reluctance to show fear (a survival instinct) with it feeling happy and content, which is something we warn against in the Basic Bird Care class.

Others within Mickaboo question the ethics of prolonging the lives of wild birds in such restrictive conditions. The suggestion to consider humane euthanasia for the most debilitated birds has sparked debate, weighing their limited quality of life against the high costs and resources required to sustain them. Tammy is opposed to euthanasia. She emphasizes the organization’s responsibility to provide these birds with the best possible life, while others argue that the WC’s prolonged dependence on medical intervention highlight the need for a more humane approach.

Additionally, as will be discussed below, concerns about the care environment at FTB have been raised. Birds seen at FTB receive excessive treatments of questionable value at considerable expense. The facility offers limited enrichment and lacks transparency, as Mickaboo volunteers have at times been unable to visit the birds.18Can’t Visit Birds at FTB The prolonged hospital stays and inability to transition these birds into more natural settings underline the need for a reassessment of Mickaboo’s approach to wild conure rehabilitation and care.

This discussion reflects broader ethical and practical challenges in balancing the mission to save wild birds with their long-term welfare and quality of life that Mickaboo, as a companion bird rescue, is not qualified to address.

Long Term Boarding

Mickaboo states that it does not operate a central bird care facility. Instead, birds in our care are housed through a network of foster homes. This decentralized model is a core part of our identity—Mickaboo proudly emphasizes that all funds are directed toward bird care, not infrastructure, and highlights the foster-based system in our public messaging. Our Organizational Structure and Policies document explicitly states that we do not maintain a facility, and that “our ability to take in birds is limited by foster home space.”

While technically accurate, this description does not reflect current practices. In reality, Mickaboo relies on two facilities where birds are regularly boarded—often for extended periods—at significant cost. As previously noted, non-medical boarding alone accounted for 22% of Mickaboo’s expenses over our two year focus period, covering just 65 birds. When including long-term medical boarding, exclusively at For the Birds (FTB), the combined cost of boarding rises to roughly 65% of the organization’s total expenditures.

Many of the birds at FTB have remained there for months or years, a situation not observed at other veterinary practices and one that appears medically unnecessary. This practice runs counter to Mickaboo’s stated mission of ensuring “the highest quality of life for our companion birds.”

Conflicts of Interest

As our financial review revealed, veterinary resources are disproportionately allocated to a small percentage of birds at a single clinic. Fosters are told that Mickaboo cannot afford routine check-ups or annual well-bird visits, despite the organization’s advocacy for preventive care in its educational materials. Yet, birds sent to FTB undergo extensive testing and examinations, with most being hospitalized for at least a day or two—some for significantly longer. A fuller account of these birds and their procedures can be found in our Focus Birds section.

Dr. Fern Van Sant maintains a long-standing personal relationship with key leadership figures at Mickaboo, which refers a majority of its avian medical cases to her clinic, FTB. Over the years, Dr. Van Sant has received millions of dollars in veterinary fees from Mickaboo, despite not holding board certification in avian medicine.

Though Mickaboo states in its “Organizational Structure“ document that “wherever possible we use board certified avian vets,” leadership at Mickaboo has consistently promoted Dr. Van Sant’s services while dismissing or minimizing the value of board-certified avian veterinarians. Volunteers who raise concerns about this imbalance or question the lack of credentialed oversight are often silenced, accused of being divisive or excluded from decision-making.

This dynamic presents a clear and ongoing conflict of interest: personal loyalty and financial dependency appear to be prioritized over bird welfare, professional standards and accountability. It has fostered a culture where scrutiny is discouraged, second opinions are rare, and serious concerns about care practices are routinely ignored.

Resistance To Criticism and Founder Interference

Amid these issues, some volunteers have called for a critical evaluation of Mickaboo’s list of recommended veterinarians and the standards by which our vets are assessed. While leadership asserts that Tammy’s extensive experience as a vet tech and her critical perspective render independent audits unnecessary,19Slack “Vet Neutral” Exchange volunteers argue that third-party assessments would help avoid conflicts of interest and ensure transparency and credibility in vet recommendations.

Mickaboo highlights the importance of using avian vets in its training materials, but they don’t provide any kind of basis for how to judge the quality of those vets. Only three of its twelve “approved” veterinary hospitals employ actual board certified avian specialists. Additionally, despite disclaimers on its website suggesting neutrality in recommending veterinarians, Mickaboo actively seeks to restrict the use of certain avian-focused vets,20Examples Available Upon Request often without employing the input of recognized specialists within their system. Although some of these restrictions might be warranted, this approach creates an impression of inconsistency and arbitrariness that limits Mickaboo’s ability to enforce organizational policies.

For example, concerns have been raised regarding the practices of certain veterinarians, including one we’ll call Vet A. Criticisms highlight issues such as the frequent prescription of antifungal medications without adequate diagnostic evaluation, reliance on potentially outdated methodologies rooted in earlier veterinary teachings, and a perceived lack of adaptation to modern advancements in avian care.

Despite these concerns, some fosters and adopters continue to utilize Vet A’s services, underscoring a lack of effective communication and enforcement of Mickaboo’s veterinary recommendations. This highlights a disconnect between Mickaboo’s internal reservations about certain veterinarians and its external messaging. While leadership has raised concerns about Vet A in internal discussions, these issues are not effectively communicated through public channels, leaving fosters and adopters without a clear understanding of why specific veterinarians are discouraged. If volunteers ask why a certain vet is excluded, they are told to contact Tammy or one of the other leaders for a private conversation.

The issue is compounded by Mickaboo’s relationship with Dr. Van Sant. Like Vet A, Dr. Van Sant has been criticized for employing questionable practices that are either outdated or lack support from peer-reviewed studies. Both Dr. Van Sant and Vet A appear to work in environments where their practices and opinions remain largely unchallenged, limiting their engagement with newer ideas or peer-reviewed input.

Veterinary progress depends on openness to new information, often fostered by collaboration with a diverse range of professionals, including new veterinarians who bring fresh perspectives and challenge established norms. A willingness to engage in dialogue, accept feedback and foster a collaborative approach is essential for growth and innovation. In contrast, defensiveness when faced with questions or alternative viewpoints, as seen in some cases, may stifle advancement and perpetuate outdated practices.

Despite similarities, Dr. Van Sant is on Mickaboo’s approved list of vets, whereas Vet A is not. This underscores the conflict of interest at the heart of Mickaboo’s operations. Michelle Yesney, Mickaboo’s former CEO and current board member, is a close friend of Dr. Van Sant and also plays a key role in protecting her position. Michelle’s daughter works at FTB. Other board members similarly maintain close ties with Dr. Van Sant and FTB, perpetuating a lack of accountability and fostering an environment that prioritizes personal relationships over objective oversight.

Furthermore, Tammy holds significant influence over Mickaboo’s medical decisions, despite lacking formal veterinary credentials. While her extensive experience as a veterinary technician is undeniably valuable, she is not a vet, and her position and influence blur the lines of responsibility and expertise. It is critical to recognize that medical decisions should ultimately rest with qualified professionals, ensuring that the organization’s standards align with its stated emphasis on evidence-based, high-quality avian care.

Establishing clear and consistent standards supported by factual explanations for veterinary recommendations is essential to ensuring transparency, credibility and alignment between Mickaboo’s internal policies and external messaging. While board certification in avian medicine could serve as a potential benchmark, it is important to recognize that Mickaboo currently supports veterinarians who lack this credential. Similarly, the use of questionable procedures could serve as grounds for restrictions, but Mickaboo’s heavy reliance on a veterinarian with controversial practices risks undermining the consistency and credibility of such standards.

About Avian Board Certification

Certain leadership figures have repeatedly dismissed or discredited the value of board certification for avian veterinarians, promoted non-certified practitioners without disclosure of personal conflicts of interest, and discouraged open discussion about credentialing and veterinary oversight. These practices present serious ethical and animal welfare concerns. A recent exchange between volunteers and leadership highlights these issues.21Dismissal of Board Certified Vets Slack Exchange Therefore, we feel it necessary to explain what ABVP is–and isn’t.

The only official requirement for treating birds as a veterinarian is a DVM degree and an interest in avian medicine. This means any licensed vet can present themselves as an avian vet, regardless of whether they have undergone specialized training. True avian board certification—comparable to specialties in human medicine—is rigorous, time-consuming, costly, and requires a sustained commitment to continuing education, scientific research and peer-reviewed standards. It is true that a veterinarian who has not achieved recognition through an AVMA approved certifying specialty may practice very good quality medicine and/or surgery, but it also is true that of those who have, there is a higher probability of balanced knowledge and skills within that specialty merely because of what is required to achieve and maintain that recognized status.

Unfortunately, there are some organizations that offer superficial credentials in exchange for a membership fee, creating the illusion of certification. Typically, these are not recognized by the AVMA or ABVS (American Board of Veterinary Specialists). As a result, consumers often have no reliable way to assess a veterinarian’s qualifications. Birds differ from dogs and cats far more than dogs and cats differ from humans—yet we would never consult a veterinarian for our own healthcare. In avian medicine, there are credentialing letters after a vet’s name that truly matter, but too often, the public doesn’t know what to look for.

Three organizations offer certification to veterinarians specializing in bird care. The American Board of Veterinary Practitioners (ABVP) is one of them. This certification is overseen by the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) and involves:

- A DVM degree

- Advanced, focused training in avian medicine (often through residency or structured mentorship)

- Submission of case logs and reports

- A comprehensive specialty examination

- Ongoing maintenance through continuing education (minimum 25 hours/year)

- Recertification every 10 years

- Peer-reviewed publications, lectures and conference participation

Unlike membership-based organizations (e.g., AAV), ABVP certification is merit-based, reviewed and maintained through independent oversight.

Mickaboo volunteers and staff who have raised concerns or asked for clarification regarding board certification and Mickaboo’s vets have been accused of being “judgmental,” “weaponizing credentials” or undermining community morale. This has created a chilling effect on honest discussion and inquiry, fostering a culture of silence around important issues affecting bird care. Moreover, volunteers are often ignored or ostracized as the board appears to prioritize protecting Dr. Van Sant over addressing valid criticisms.

Publicly dismissing the value of board certification—while relying heavily on a non-certified vet with personal ties—puts the organization’s credibility, reputation and bird welfare standards at risk. It also opens the door to legal and ethical scrutiny from donors, adopters and the veterinary community.

Although board certification is not the only criteria by which scientifically balanced acuity of care can be measured, it is a recognized standard in many venues. Non-certified avian vets can, and do, provide excellent care. However, the complexity of Mickaboo’s long-term and challenging cases highlights the need for a structured, team-based approach guided by a recognized avian specialist to ensure birds receive balanced, forward-moving care.

Care and Welfare Concerns

Exceeding Our Intake Capacity

A significant challenge Mickaboo faces is overcrowding. This is largely due to Mickaboo’s deep desire to help as many birds as possible, coupled with a lack of foster or adoptive homes. As animal rescuers, turning away birds in need is antithetical to our nature. Several practices compound the problem: taking in birds without available foster homes; taking in birds who are not from poor environments, whose owners simply don’t want them anymore; volunteers searching shelter listings to find birds; working with third parties when owners are not incapacitated; and, less frequently, incubating and hatching eggs encountered during bird rescues.

We currently have three locations in which significant overcrowding exists. Sarah Lemarie reportedly houses over thirty birds in her duplex, including fifteen wild conures. Dr. Renee Luehman has twenty-five birds, including ten wild conures. The third location is FTB, where approximately thirty birds live or spend considerable time in the back of the facility–and those are just Mickaboo birds.

Exceeding capacity can create significant problems. Birds require individualized care, attention and observation to thrive. Most species also need considerable human interaction to remain comfortable in a human-centric environment. Providing this level of care is difficult even with a dedicated team of three to four people when managing so many birds in one location. In situations where over a dozen birds are housed in a single home, they may survive and stay physically healthy but are likely only receiving the bare minimum of care. Over time, this can negatively impact their socialization skills and overall health.22Birds turning “Feral”

Overcrowding also limits the space birds need to play and move safely, especially when different species are housed together. Birds of varying social dynamics can experience heightened stress when confined to shared, crowded environments. This stress, compounded by inadequate space, can lead to behavioral issues and discomfort. Additionally, the dander produced by birds can quickly degrade indoor air quality, potentially triggering allergies or respiratory issues in both birds and humans. Managing this becomes significantly harder as the number of birds in an enclosed area increases.

Maintaining proper quarantine measures in overcrowded conditions is nearly impossible, especially when birds and people frequently move in and out of the space. A single communicable disease in one bird can easily spread to the entire household, putting all the birds at risk. Furthermore, birds require daily cleaning of their cages and environments to ensure hygiene and health. The more birds in one location, the harder it becomes to meet these basic standards of care, leading to unsanitary conditions and potential health risks for the flock.

The most significant cause of overcrowding is taking in birds when there are no foster homes available, especially if the bird has not been abused, is not in a poor environment and is with an owner that simply doesn’t want it anymore. In these situations, surrenderers are using Mickaboo to do what they could do themselves–rehome a bird–especially if Mickaboo provided guidance on how to vet potential adopters.

Secondly, certain Mickaboo volunteers routinely trawl through shelter listings to find birds. Despite the strain on our resources, we often initiate contact with shelters where birds have been surrendered, rather than waiting for the shelters to reach out to us—as they are supposed to do when they need assistance. This approach is not only inefficient, it undermines our relationships with shelter staff. In fact, when we proactively contact shelters about birds they are not ready to release, it can alienate them and discourage future collaboration.

Furthermore, we often respond to third-party requests to take in birds without the owner’s knowledge or permission. While it is appropriate to act in situations where the owner is deceased or incapacitated, in all other cases, we must wait for the owner to contact us directly. Our eagerness to intervene has, in the past, led to accusations that Mickaboo was stealing birds—damaging both our reputation and our credibility.

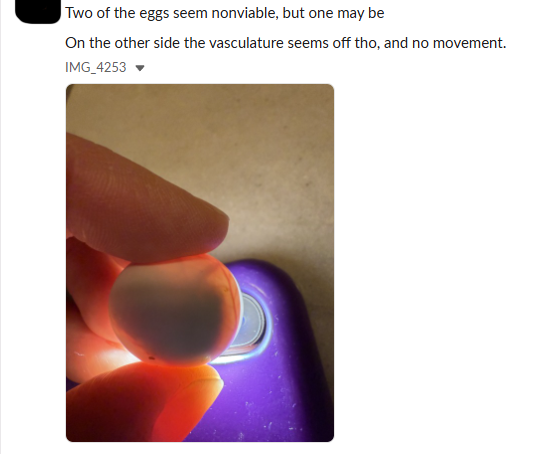

Another concerning practice is the incubating and hatching of eggs found in nests during rescues. This contradicts Mickaboo’s ethos of discouraging breeding. We are not sure how often this happens, because as with everything in Mickaboo, the practice is opaque. In fact when a volunteer brought up the subject, Tammy responded, “Who’s hatching eggs.”23Slack: Who’s Hatching Eggs? Because if someone in Mickaboo were hatching eggs, she’d want to know. However, there are references to it in Slack conversations24nest of eggs25Hatching eggs and, during a large rescue, at least one volunteer was tasked with finding viable eggs.

These practices, driven more by impulse than by policy, have strained our relationships with shelters and private parties alike, and contribute to the very overcrowding that undermines our mission.

Extended Foster Periods

Although Mickaboo maintains that birds are only accepted when foster homes are available, in practice this policy is inconsistently applied. Many new applicants who intended to adopt end up becoming fosters instead. Rather than focusing on placing long-term birds into permanent homes, new intakes are often prioritized.

As a result, a large number of birds remain in foster or supportive care for extended periods. Of the approximately 450 birds currently in our system, around 300 have been with Mickaboo for over two years, and roughly 150 have been in care for more than three years.

The result is that many birds spend years moving through a series of foster homes, contrary to Mickaboo’s stated commitment to ensuring permanent placements.

For example:

- Ethel, an Amazon, has been with Mickaboo since September 2005. She has been moved seven times, including two adoptions followed by returns.

- Cinnamon and Spice, cockatiels brought in during 2010, have cycled through eight foster homes and spent four months at FTB.

- BJ, another Amazon, has been moved nine times over the past twelve years.

These frequent transitions are highly disruptive to the birds’ emotional well-being, especially given that parrots form strong bonds with their caretakers. Being repeatedly relocated causes stress, confusion and behavioral decline. Even when birds remain in one foster home for years, failure to bond or lack of preventive care suggests their needs are not being fully met.

Another concern involves fosters who don’t adopt long-term fosters primarily so Mickaboo continues to cover veterinary expenses. While this is appropriate for birds who qualify for hospice care, in other cases it’s an abuse of the system. For instance, Rowan, in Mickaboo’s care since January 2009, has remained with the same foster for over 15 years. In that time, Mickaboo has spent more than $16,000 on his care, unsurprisingly at FTB, including substantial boarding costs. These practices not only strain Mickaboo’s financial resources but also raise serious ethical and conflict-of-interest concerns.

Some fosters do not actively communicate with coordinators, participate in adoption efforts, or make birds available for meet-and-greets with potential adopters. This lack of engagement impedes our ability to place birds in permanent homes and undermines our mission.

Moreover, fosters are often not informed that birds may remain in their care for several years, rather than the few months they were led to expect. In some cases, this has resulted in fosters threatening to surrender birds to animal shelters unless Mickaboo intervenes immediately—situations that could be avoided with better communication and planning.

Addressing these issues is essential to realigning Mickaboo’s practices with its mission. We must prioritize transparency with fosters, ensure accountability in long-term placements, prevent abuse of financial support systems and renew our commitment to finding permanent homes where birds can truly thrive.

Lack of Preventive Vet Care

Much as it is in humans, preventive care is essential to maintaining a bird’s health and well-being. This includes regular visits to an avian veterinarian, which can help caretakers avoid costly emergencies down the line. One of the strongest arguments for preventive care is how subtly birds display signs of illness, often masking problems until they become serious. Access to avian emergency care is limited, and well-qualified avian veterinarians may not be available when crises hit—often during holidays or after hours.

Though annual exams have upfront costs, they are often cheaper and more effective than treating advanced illness. A strong relationship with a knowledgeable vet is vital, allowing for early detection of hidden issues, establishing health baselines and receiving expert guidance on your bird’s environment and behavior.

However, Mickaboo consistently fails to provide preventive care for birds in its system. Routine wellness checks are not covered, even when requested by fosters or funded by specific donations. Mickaboo birds in long term foster care are not receiving the most basic preventive care that we demand from adopters. This undermines the organization’s ability to support long-term well being for the birds in its care.

A recent example26Records available upon request to interested parties. is Sweeney, a foster Senegal parrot who suffered a seizure-like episode several weeks ago. He had not received a wellness examination in the nearly ten years he’s been in foster care. The attending veterinarian expressed dismay and noted that many of the Mickaboo birds he treats are similarly overdue for their annual health evaluations.

The fact that a bird requiring urgent medical attention had not seen a veterinarian in a decade is a serious indictment of the organization’s standards of care.

In practice, when foster birds require medical attention, foster volunteers must navigate a convoluted and time-consuming approval process—one in which communication is often inconsistent or dropped entirely. This frequently results in significant delays in obtaining necessary care, despite the fact that Mickaboo’s foster agreement explicitly permits emergency veterinary visits without prior approval. In reality, fosters are given little guidance on how to determine what constitutes a true emergency, leaving many uncertain and hesitant in critical moments.

Control Without Responsibility

Mickaboo’s adoption contract attempts to exert an extraordinary degree of control over how adopters care for their birds, while simultaneously disclaiming responsibility for the birds’ long-term welfare.

A significant number of potential adopters have expressed discomfort with the contract, particularly the clause requiring organizational approval for euthanasia. For many, this is the primary reason they ultimately decide not to adopt.

As stated in the contract: Euthanasia must first be discussed with and approved by an MCBR director prior to the procedure taking place. This requirement remains effective for the lifetime of the Bird.27Mickaboo’s Adoption Contract

This policy is not only overly intrusive—it is, in practice, unworkable. Tammy, the director who insists on personally approving all euthanasia decisions, is often too overwhelmed to return calls, creating distressing delays in situations that require compassion and timeliness.

In January of this year, a volunteer28More information available upon request found themselves at an emergency veterinary clinic at 4 a.m. with a critically ill bird who was clearly near the end of its life. Given the circumstances, they made the humane decision—together with the attending veterinarian—to proceed with euthanasia without waiting for organizational approval.

The volunteer later reflected on how unworkable Mickaboo’s policy truly is, noting the absurdity of expecting someone to call a director at 4 a.m. for permission in such a situation. They emphasized how distressing it would be for an adopter to watch their bird suffer while waiting for a return call from leadership.

Another example involves a volunteer29More information available upon request caring for a terminally ill cockatiel. Although the adoption contract required consultation with Mickaboo regarding euthanasia, the volunteer intentionally chose not to reach out. Based on prior experiences and knowledge of the director’s strong opposition to euthanasia, they feared the bird would be taken back, subjected to surgery, and made to suffer further.

Instead, the volunteer prioritized the bird’s welfare and made the difficult decision to proceed with euthanasia. A necropsy later confirmed that the bird would not have survived the surgery, validating that the decision was both compassionate and medically sound.

The degree of control Tammy exercises over medical decisions for birds in Mickaboo’s care is a key factor contributing to excessive and often unnecessary medical interventions at For the Birds (FTB).

Questionable Veterinary Practices

A specific point of concern is Dr. Van Sant’s frequent reliance on hormonal treatments as a first-line intervention, a practice not aligned with some of the latest veterinary literature. Dr. Van Sant routinely prescribes Lupron for every bird displaying feather picking or normal hormonal behaviors, such as regurgitation. More concerning is the use of deslorelin implants, an FDA-indexed product, which is specifically prohibited for use in anything but ferrets.

This blanket approach is not supported by avian experts, as counter hormonal treatments should not be the first line of defense for such issues. Many board certified avian veterinarians emphasize the importance of addressing behavioral problems on a case-by-case basis (behavior is the study of one) and staying current with advancements in avian medicine. Attributing unexplained or non-specific clinical signs to hormonal issues by default can easily reflect outdated or incomplete methodologies based on personal observations or experience rather than peer-reviewed evidence.

Dr. Van Sant has also advocated for separating bonded pairs of birds as a response to chronic egg-laying in females.30Examples available upon request This practice can be viewed as both cruel and unnecessary, as there is no evidence that by removing the male, egg-laying can be prevented. Females can and do lay eggs without a male present, as other stimuli are also involved with activation of that hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Leadership downplays the strength of pair bonding, though such separation inflicts needless distress on the birds, which form lifelong bonds. This approach disregards their emotional well-being and welfare, which are essential aspects of good husbandry and veterinary health care.

Similarly, Dr. Van Sant discourages the use of shredding or chewing materials and recommends removing bells from cages to prevent hormonal stimulation. These recommendations conflict with widely accepted avian care practices, which recognize shredding, chewing and play as vital to a bird’s mental and emotional well-being. Such enrichment activities are integral to preventing stress-related behaviors such as feather picking, and their restriction raises more concerns about the quality of care being advocated.

Another troubling issue involves dietary recommendations, including the promotion of high-potency pellets for adult african grey maintenance, exclusive recommendations for the use of specific brands, and reliance on Nutri-an Cakes, which are only available through veterinarians, specifically Dr. Van Sant. This creates dependency on certain products without evidence of their necessity or value as a dietary staple. High potency diets have significantly elevated fat in their makeup and high fat diets are a recognized long-term health risk factor for Grey parrots and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in general. Dr. Van Sant also advocates for meal feeding–the practice of feeding a bird just twice a day–another unnecessary deprivation-related treatment generally only appropriate for sick or overweight birds under the close watch of a vet, that can lead to digestive issues.

Further scrutiny surrounds the transparency of FTB operations. Volunteers report being denied access to certain areas of the facility and having inquiries about birds go unanswered. In a Slack exchange from January 2024, Sarah voiced frustration over the number of birds Mickaboo continues to board without FTB providing regular updates, including several wild conures. She questioned the claim that none of these birds were ready for discharge and noted that FTB makes it unnecessarily difficult to transition them into foster homes. This lack of responsiveness and accountability is a significant red flag for an organization that should prioritize open communication about the animals in its care. Given that the birds at FTB are Mickaboo property, it also raises questions of legality.

Lack of Behavioral Training, Inadequate Vetting and Follow Up

Mickaboo’s processes for vetting, training and follow-up often fall short, leading to significant issues in foster and adoptive placements. Potential fosters and adopters are frequently insufficiently screened, resulting in placements with individuals who may misrepresent their circumstances, fail to absorb training materials, or exhibit warning signs that are overlooked during the application process. Additionally, coordinators often neglect to review previous records before placing additional birds with fosters or adopters, allowing recurring problems to persist.

Mickaboo does not provide adequate training to fosters and adopters to address behavioral challenges, particularly for complex species like grey parrots, Amazons, macaws and cockatoos. These birds are often placed with inadequately experienced individuals, leading to their return after behavioral issues arise. Targeted, evidence-based behavioral interventions, both reactively as well as proactively, would significantly aid in addressing these issues, but fosters who wish to help their birds must pay for their own behavioral consultations.

Many behavioral issues—such as feather plucking, screaming and aggression—develop gradually in response to chronic stress, boredom or unmet social needs. These problems are frequently avoidable with proactive measures such as proper socialization, enrichment and training from an early stage. However, few adopters or fosters are educated on these needs, and behavioral concerns are often addressed only after they become severe. Without early intervention, these behaviors can become entrenched, reducing the bird’s adoptability and overall welfare.

Mickaboo often prioritizes convenience for humans over what is best for the birds in its care. Rather than investing in behavioral training to address issues like feather picking or aggression, the organization frequently attributes these behaviors to hormonal imbalances and turns to pharmacologic interventions such as Lupron injections or deslorelin implants. While these treatments may have valid applications in some cases, they are significantly more invasive and costly than behavioral approaches—and ultimately less effective in promoting long-term change.

In cases of egg-laying, for example, it is easier to break up bonded pairs and administer hormonal treatments than to implement environmental and behavioral modifications that would naturally reduce laying. This tendency reflects a broader pattern: relying on medical interventions rather than addressing the root causes of behavioral issues through changes in diet, environment and social structure.

Pharmacologic treatments like Lupron and deslorelin do suppress hormone production and, by extension, the behaviors associated with it—but only temporarily. These drugs do not help birds learn alternative, healthy behaviors. In fact, by masking the behaviors, they can make behavioral intervention more difficult, as trainers are unable to observe and work with the problem directly.

The issue stems, in part, from a lack of training in behavioral medicine. Most veterinary programs offer minimal instruction in applied behavioral analysis, leaving practitioners ill-equipped to manage behavior issues scientifically. Additionally, the cyclical nature of these treatments, which require ongoing administration, can inadvertently incentivize repeat procedures—especially when short-term results are interpreted as success.

Ultimately, while hormonal treatments may have a role in specific cases, overreliance on them reflects an incomplete understanding of avian behavioral health and a missed opportunity to support birds through more sustainable and humane methods.

Extended Hospitalization

Another problem is the issue of long-term hospitalization that occurs exclusively at For the Birds. While it is normal for vet clinics to hospitalize birds for the short term or board them for clients, the situation at FTB deviates significantly from standard practices. Birds often check in and never leave. There have been problems with Mickaboo coordinators not being able to see the birds. As shown above, internal communication shows that Mickaboo’s board is well-aware of the problem.

As of April 2025, there are approximately thirty birds boarding or hospitalized at FTB: one amazon, one african grey, five cockatiels, fifteen wild conures, three finches, four parakeets, a green cheek conure and one green wing macaw. Twenty-eight of those birds have been there longer than a month. Eleven have been there between a month and a year; five between one and two years, four between three and four years, five over five years, and one, Muriel, an African grey who arrived on 8/8/13, has been there over eleven years.

We have observed numerous cases where a bird is initially treated at one veterinary clinic before being transferred to FTB for a “second opinion.” Once there, the bird undergoes many often questionable tests and procedures and in some cases remains at the clinic for years. Reciprocal “second opinions” appear to be exceedingly rare, and are not accompanied by extended stays at other vet clinics.

Muriel

Muriel came to Mickaboo on November 1, 2010, with severe trauma to her right wing tip. Initially treated with wound debridement and a bandage, she repeatedly removed the bandage and self-mutilated, prompting a mid-antebrachial amputation to prevent further injury and stabilize her condition.

Between November 14, 2010, and December 10, 2011, Muriel was treated for self-mutilation at Medical Center for Birds. Her care included the use of a cervical collar, medications such as Haloperidol, Omega-3 FA and Metronidazole, and a behavioral management plan incorporating foraging strategies to encourage positive behaviors. While her foraging skills and overall behavior improved, her prognosis for overcoming self-mutilation and living without a collar remained uncertain. Upon discharge, she was prescribed pain and anti-inflammatory medications, as well as antibiotics, but concerns persisted that further self-mutilation could necessitate another amputation. It was advised that she remain caged to prevent additional injury.

In late 2011, Muriel’s new foster took her to another vet, whom we’ll call Vet D, where it appears she faced the possibility of another amputation. Tammy suggested obtaining a second opinion from Dr. Van Sant before proceeding with surgery. Concerns were raised by her foster parent regarding Muriel’s stress levels, as boarding had previously led to increased self-mutilation. Tammy acknowledged these concerns and proposed an alternative approach involving an exam and review of her veterinary record.

Muriel was seen on March 6, 2012. She received Lupron, a deslorelin implant and a series of diagnostic tests. Despite these measures, the amputation surgery appears to have taken place on March 15, and Muriel was subsequently boarded for one to two weeks. Muriel was adopted by her third foster on 8/04/2012.

On August 8, 2013, Muriel was surrendered by her adopter, who was unable to stop her self-mutilation and expressed concerns about her quality of life, wanting the best possible care for her. Muriel was transferred to FTB, where she has remained in “short-term care” ever since. While she has not incurred boarding costs at FTB, her care costs since March 28, 2012, have amounted to $16,000.

According to FTB, Muriel’s situation today is more stable. She is the “office bird” at FTB. She wears a collar daily, but gets time without it. Oral diazepam stops the mutilation, but clearly sedaties her, and doesn’t work as a long term solution. Because of her special needs, Dr. Van Sant says she will likely never be “adoptable.” There are no reports of any targeted behavioral assessments or interventions that we can find to support these assumptions.

Boomer

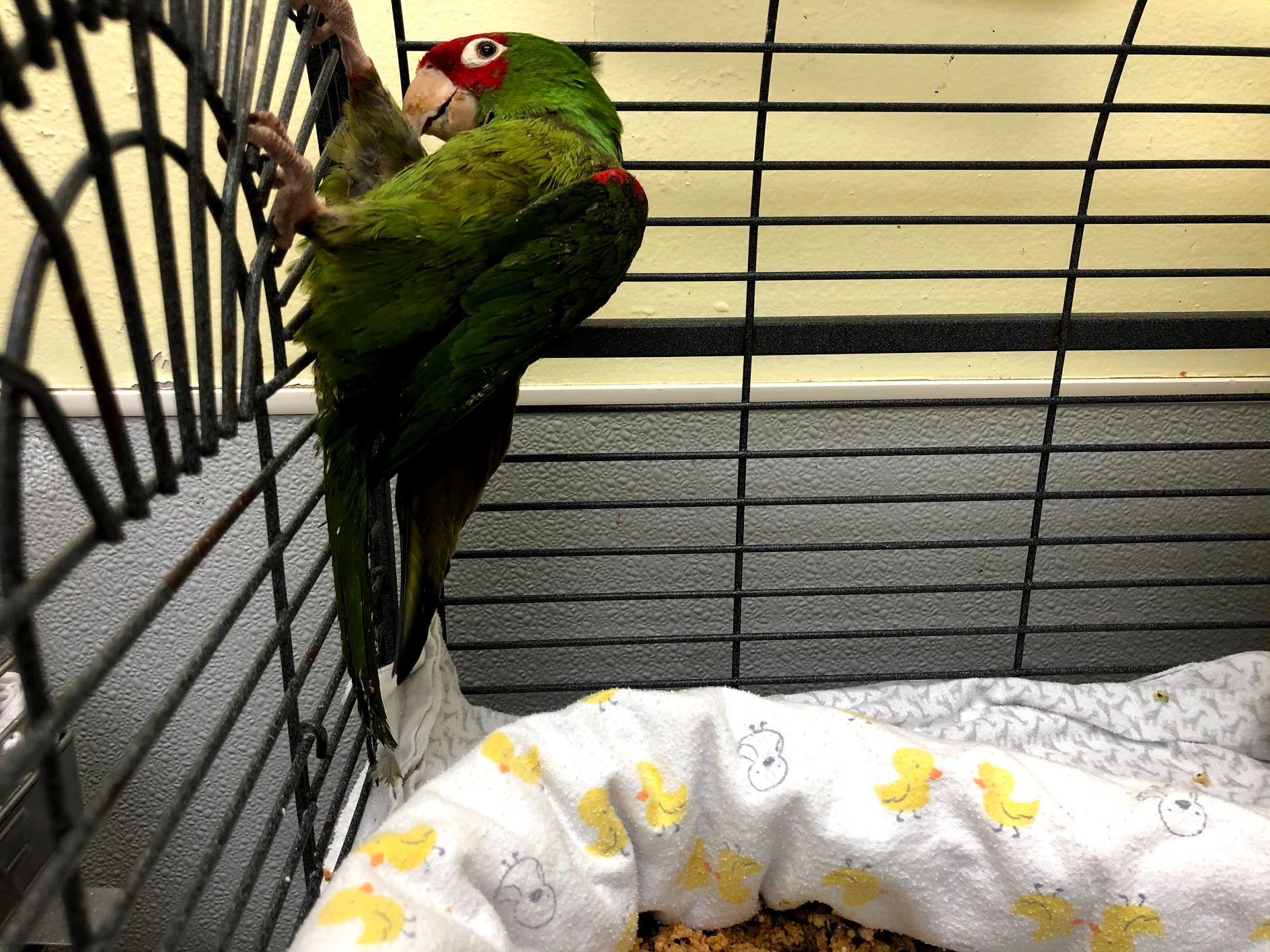

Boomer, a Green-wing Macaw, came to Mickaboo in October 2012 after years of severe neglect. He had suffered from untreated injuries, malnutrition and socialization challenges. Upon intake, Boomer exhibited significant physical impairments, including fused joints, dislocated limbs and severe intestinal issues. Despite his disabilities, he responded well to care at MCFB, undergoing a successful pygostyle amputation in 2013 to improve his quality of life. Boomer thrived in foster care for a number of years, becoming more active, social and vocal, with a noticeable improvement in his overall well-being.

After the sudden death of his long-term foster in 2019, Boomer was transferred to a new foster. In 2020, he went to FTB to address recurring intestinal issues, which had already been addressed years before at MCFB. Since his arrival at FTB, he has received extensive treatments and procedures, including Lupron injections and ongoing care for malodorous droppings and seizures.

While Boomer’s total veterinary costs from 2012 to 2020 were $7,270, his care at FTB has accrued an additional $105,000, bringing his total expenses to $112,270. Despite the significant investment in his care, questions remain about the necessity and efficacy of some treatments and his placement at FTB, given his prior progress in foster care.

Neglect of Challenging Birds

While all birds need similar care in terms of diet, environment, enrichment and companionship, some species are far more complex and challenging than others. Placing a challenging species with someone who has never had birds before without proper training or follow up can have devastating consequences for the bird. Some of these birds have been relegated to FTB and essentially forgotten about.

Max

Max, an African Grey, came to Mickaboo in September 2017 after being surrendered by his previous family. He was a beloved companion but they felt he would be happier in a more suitable environment, citing signs of stress due to the presence of other African greys in their household. Entrusting Mickaboo with his care, they hoped to provide Max with a better life.

Unfortunately, Max’s journey proved challenging. His first adoption placed him with an inexperienced individual unfamiliar with African Greys, resulting in aggressive behavior and his return. Over several months, Max moved between multiple foster homes, none of which successfully addressed his needs. Labeled as irrevocably aggressive, he was transferred to FTB and subsequently passed to another rescue organization, which later ceased operations. Max returned to FTB on September 16, 2019, where he remained until July 27, 2024.

In July, Mickaboo’s African Grey coordinator found a foster willing to take Max, despite warnings from FTB and Mickaboo leadership about his history of significant aggression. Described as unpredictable and quick to lunge, FTB claimed Max required a high level of caution during handling. He was only allowed out of his cage for routine examinations, which were conducted using a towel in the dark. The foster was asked to sign a waiver acknowledging these challenges.