Focus Birds

We’ve chosen a few representative birds to illustrate our overall findings. These are birds who have been living at FTB, incurred the highest costs, or who otherwise illustrate some of Mickaboo’s failings. There are many others examples. Amount of information on individual birds varies dramatically. We’ve tried to incorporate all information we’ve found, but very little is recorded for some of these birds. Use the links to the left or scroll down for information on each bird.

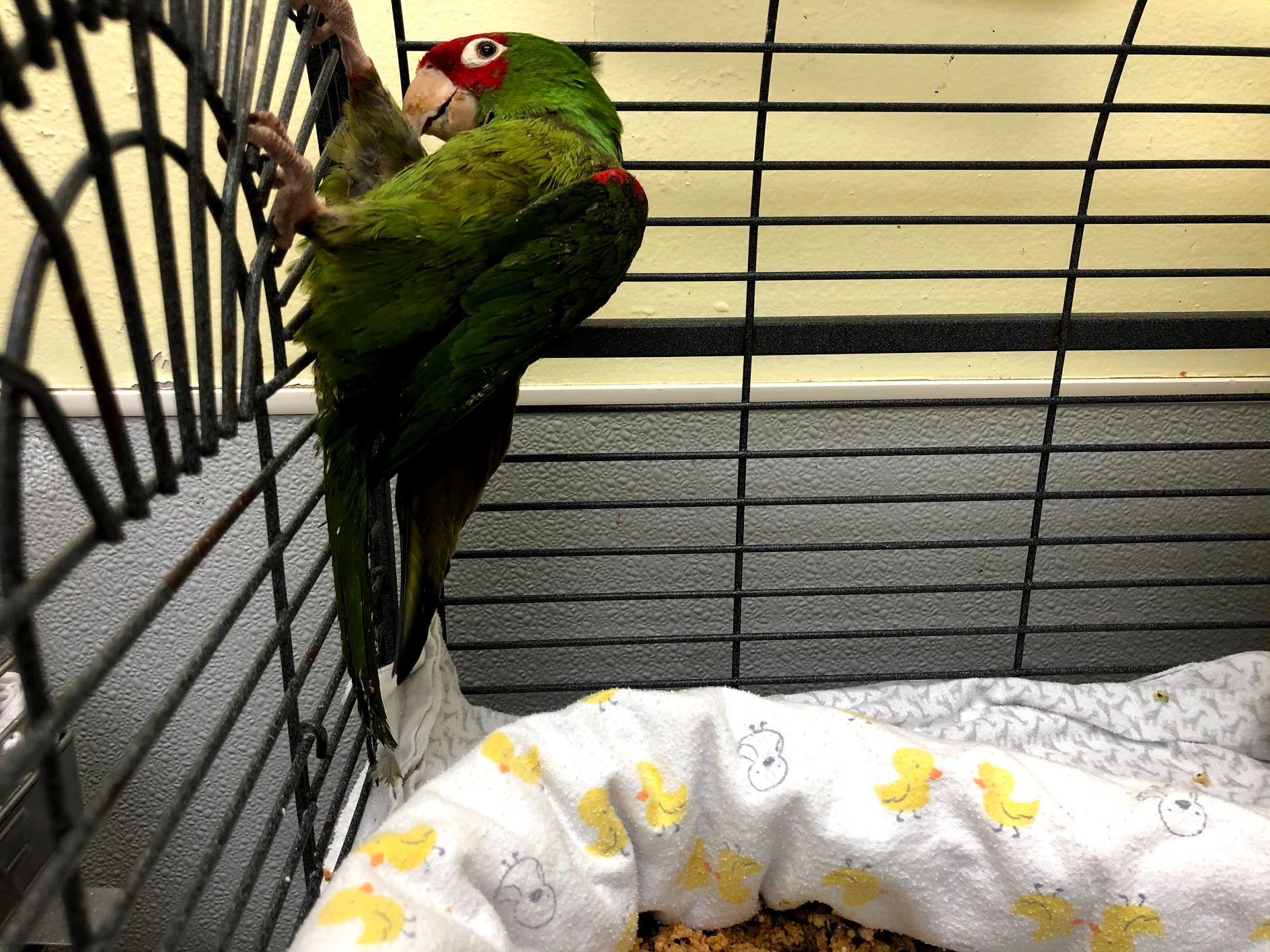

Wild Conures

There are currently six1See here for an email exchange regarding them, from 2024 severely debilitated conures being kept at FTB: Billy, Bartol, Martin, Bowley, Rico and Winston. Five are assumed to be bromethalin survivors and one (Martin from the Sunnyvale flock) is probably the survivor of an animal or bigger bird attack.

As a group, these birds are unable to perch but can manage on flannel bedding with towels rolled in flannel along the cage perimeter. Bromethalin appears to impact the nerves that enable the cloaca to pass feces, and they are prone to fecal retention and clostridial overgrowth. They can require assistance defecating. FTB treats them proactively after one conure (Nino 1/2022) developed a fecal impaction of the colon and cloaca that completely obstructed his GI tract.

Historically these birds were treated with oral Celebrex, a COX 2 anti-inflammatoy. This treatment was eventually replaced with weekly injections of robenicoxib (Onsior), a long acting COX 2 veterinary drug. They are fed crushed pellets with applesauce, Miralax (an osmotic stool softener) and pancreatic enzymes. They get an assortment of fresh fruit and veggies as tolerated, and receive antibiotics for clostridial infections when needed. Vitamin AD3E injections are given monthly. Most require regular beak and nail trims. The need for beak trims is likely the result of the severe face, head and beak trauma that they sustained.

Billy

Billy was found collapsed on a fire escape, likely after a confrontation with other birds. He has been under FTB’s care since June 1, 2018, with treatment costs totaling $70,621. Upon intake, he underwent bloodwork at Bay Area Bird Hospital, before being transferred to FTB. Films of his heart showed dense particles, and he tested positive for lead, leading to chelation treatment. Billy was also placed on Cipro antibiotics, fluids and gavage feeding, showing signs of improvement as he began eating on his own. Tests were also conducted for bromethalin poisoning, which was confirmed.

On September 10, 2018, Sarah expressed surprise that Billy was still alive, as she had not seen him during previous visits. He was kept in the hospital room and partially covered to prevent self-destructive behavior due to his tendency to startle easily. By February 9, 2019, Sarah noted that Billy seemed less distressed and had moved from the back of his cage to the center, staying upright throughout her visit, which was a positive step. The most recent update, from January 13, 2024, reported that Billy startled and fell while hanging upside down in his cage, losing several tail feathers.

Bartol

Bartol has been under FTB’s care since August 29, 2020, with treatment costs totaling $59,000. On September 1, 2020, Sarah noted significant improvement, suggesting possible head trauma. By September 13, 2020, Bartol was upright, eating and maintaining his weight. However, as of March 5, 2021, Bartol remained “under watch” and on a heating pad. He sometimes seizes when handled, and falls from his hanging position (his preferred method of “perching”), which requires soft surface. We have no more information about Bartol or his condition.

Martin

Martin has slight ataxia, feather loss, is wobbly and cannot navigate a normal cage. Martin has been under FTB’s care since July 31, 2021, with treatment costs totaling $44,061. Martin was initially taken to the Wildlife Center of Silicon Valley after being found in poor condition.

Bowley

Bowley has been at FTB since July 2020, and in that time has accrued nearly $80,000. He is severely ataxic, unable to preen/clean himself, unable to control basic motor functions and requires flannels and bumpers around cage.

Rico

Rico has moments of severe ataxia but can sometimes control basic motor functions. He came into FTB 7/29/19 after eleven days at BABH. Total FTB costs are nearly $70,000. On 7/27/19, Tammy gave a brief update regarding Rico’s condition and requested clarification on whether there had been any plans to transfer him from BABH. Rico had shown notable improvement in recent days; he was walking well, appeared alert and inquisitive and had been generally more responsive. However, that morning he experienced an unusual episode while being handled for fluid administration. During the procedure, Rico began gaping and appeared disoriented. He was released immediately, and the vet conducted an examination. She noted a potentially abnormal heart sound, which she indicated could have been stress-related or suggestive of an underlying cardiac issue. As a precaution, Rico was placed on oxygen and scheduled for reevaluation later that day.

That evening, Rico’s condition had improved significantly, and his treatments were resumed. Despite the improvement, the doctor remained concerned about the possibility of cardiac involvement and recommended continued monitoring. Although she had initially planned to pursue radiographs, that plan was deferred, with the expectation that Dr. Van Sant would determine the appropriate next steps.

Winston

Winston was taken to FTB upon intake to Mickaboo in December 2021, where he remains as of April 2025. The only information we have about him is that he walks on his hocks and needs a cage lined with flannel to avoid leg injury. His costs have reached nearly $43,000.

Poppy and Lilac

Both birds sustained severe back trauma and fractures of the caudal spine. Both have mobility problems but Lilac has adapted to perches and a regular cage. Poppy still does not have control over her legs and requires a flat flannel bedding and routinely needs help eliminating due to nerve and muscle damage.

Lilac, a 2023 fledgling, has been under the care of FTB since October 20, 2023, with treatment costs totaling $13,776. Lilac was found repeatedly falling to the ground in San Francisco and was picked up by a concerned individual who contacted Animal Control. Mickaboo then facilitated her immediate transfer to FTB for evaluation.

Poppy has been under FTB’s care since September 25, 2021. She was found struggling on the ground with apparent spinal trauma. Diagnostic evaluations revealed multiple fractures in the lumbar, thoracic and caudal spine, leaving her with little to no function in her legs. To date, her care has incurred $49,645 in costs. Despite her severe injuries, Poppy is receiving pain management, fluids, antibiotics, and wound care, with some improvement noted in her eating habits.

Poppy has multiple sites of back trauma/ fractures in the lumbar and thoracic spine and caudal spine. There has been little to no improvement in the function of either leg. Poppy’s condition presents significant challenges. Poppy’s injuries are complex and include poor vascular tone, a bowed femur and a displaced knee. Her treatments include injectable diazepam and butorphanol, which have helped her remain calmer and eat better. She also receives lupron and needs help pooping. Ongoing monitoring and potential physical therapy may offer further insights into her ability to regain function, though her long-term outcome is yet to be determined. Van Sant remains cautiously optimistic, noting the unpredictable nature of recovery in birds and the potential for improvement over time with continued care.

Kansas

Kansas entered Mickaboo and FTB on 11/30/23. All we know about him is that he has a considerable left sided wing droop, which is permanent and makes him unreleasable. His stay at FTB as so far amounted to $21,000.

Angel (Cockatoo)

Angel, a goffins cockatoo, came to Mickaboo in January 2016 when her owner of 35 years died. She was not hospitalized or boarded at FTB, but we’re using her as an example of a bird that does just fine when she no longer receives care at FTB. She was seen at FTB and for the first few years given Deslorelin implants and the occasional lupron shot. Starting at the end of 2019, she was switched to a regimen of lupron shots every two weeks, accompanied by brief exams. She was also periodically given Butorphanol/diazepam injections, HCG injections, and itraconazole and enrofloxacin. Her total vet costs between intake and 10/28/21 amount to $9,767. Angel’s long-time foster parent adopted her in October of 2021. Since then, Angel has been receiving veterinary care from a different provider and has not received any more Lupron. She is, by all appearances, doing fine.

Boomer

Boomer’s Rescue and Recovery2View the PDF

See Boomer’s full story here

Boomer, a severely neglected Greenwing Macaw, was discovered in late 2012 by a paramedic who alerted former Mickaboo volunteer Darcy Howard. Boomer had lived in squalid conditions for 25 years, surviving on an unhealthy diet and without any veterinary care. When rescued, he was malnourished, almost entirely blind, heavily plucked, had a cataract, severely overgrown nails and showed signs of long-term physical trauma, including deformed and arthritic legs, a broken wing, and a pressure sore caused by a malformed tailbone.

Veterinarians were initially unsure if Boomer would survive. He required intensive veterinary intervention, including tube feeding and treatment for chlamydia. Over time, his health and spirit improved, and he began to explore, play and engage with his foster family. A later evaluation at the Medical Center for Birds revealed the full extent of his physical damage, including dislocated joints and fused bones. To improve his quality of life, he underwent surgery to remove the end of his tailbone, which helped him poop more comfortably and reduced pain.

Boomer with his foster family.

Despite his significant disabilities, Boomer adapted remarkably well. His foster family built a special mobile platform so he could join in family life and spend time outdoors. He became active, vocal, playful and social—earning the nickname “Boomer the Buttless Wonder.” For a long time, Boomer served as a Mickaboo ambassador, bringing joy and inspiration wherever he went. He remained in foster care with a devoted family who ensured he lived a full and happy life until his foster dad died in August 2019.

He was with another foster until July of 2020. That month, Boomer was transferred to For the Birds (FTB) for chronic gastrointestinal issues, including malodorous, projectile droppings and suspected viral illness. He has remained there ever since.

Boomer at FTB

Soon after arriving at FTB, Boomer was given Lupron—commonly used there for birds that pluck, regardless of confirmed hormonal cause. Over the next two years, he underwent periodic diagnostics and treatments, including additional gram stains, fecal testing and DNA microbiome analysis. In November 2022, these tests were repeated for continued “malodorous droppings,” but since then his ongoing care has consisted mainly of daily unspecified treatments, twice-monthly Robenacoxib injections, and three diazepam injections for apparent seizures.

From 2012 through his transfer to FTB in 2020, Boomer’s veterinary expenses totaled $7,270, including one surgery. Since entering FTB’s care, his vet costs have soared to $85,000. His total veterinary expenses under Mickaboo now exceed $92,000, with the vast majority incurred at FTB—despite little evidence of progress or a clearly defined treatment plan.

The “Permanently Damaged” African Greys

Over the years, several African greys3Permanently Damaged Greys with supposed severe physical and behavioral challenges have been placed under Dr. Van Sant’s long-term clinical care. One, Merlin, was euthanized after 10 years of living at FTB when “all treatment options were exhausted.” Kai-Lan, another “elderly, medically fragile” grey was kept at FTB for seven years before dying of renal failure. Muriel remains there after eleven years. It’s important to note that these outcomes are based on Dr. Van Sant’s interpretations of their conditions, often framing these birds as permanently damaged. This perspective may be contributing to the very challenges she is attempting to “solve.”

Muriel

Muriel4Records available upon request was admitted to Mickaboo on November 1, 2010, with severe trauma to the tip of her right wing. According to records, her original owner found her in an aviary already injured. Initial treatment at the Bay Area Bird Hospital involved debridement of the wounds and application of a bandage. However, Muriel repeatedly attempted to remove the bandage and engaged in self-mutilation. Due to these complications, a mid-antebrachial amputation of her right wing was performed to remove the damaged portion and prevent further injury.

Muriel was treated for self-mutilation at the Medical Center for Birds between November 14, 2010 and December 10, 2011. In late 2011, Muriel’s new foster took her to another vet’s office, where it appears she faced the possibility of another amputation. Tammy suggested obtaining a second opinion from Dr. Van Sant before proceeding with surgery. Concerns were raised by her new foster regarding Muriel’s stress levels, as boarding had previously led to increased self-mutilation. Tammy acknowledged these concerns and proposed an alternative approach involving an exam and chart review. Muriel was seen on March 6, 2012, during which she received Lupron, a deslorelin implant and a series of diagnostic tests. Despite these measures, the amputation surgery appears to have taken place at FTB on March 15, and Muriel was subsequently boarded for one to two weeks. Muriel was adopted by her foster on 8/04/2012, after spending time in three foster homes.

On August 8, 2013, Muriel was surrendered by her adopter, who was unable to stop her self-mutilation and expressed concerns about her quality of life, wanting the best possible outcome for her. Muriel was immediately transferred to For the Birds (FTB), where she has remained in “short-term care” ever since. While she has not incurred boarding costs during her time at FTB, her treatments since March 28, 2012, have totaled $16,000.

According to Dr. Van Sant: in 2023 her situation was more stable. She is now the ‘office bird’. She wears a collar daily, but gets time without. Oral diazepam apparently stops the mutilation, but is clearly sedating her, and doesn’t work as a long term solution. She is highly demanding and will likely never be ‘adoptable’.

Evie

Evie, an African Grey, entered Mickaboo’s care on July 16, 2020. After just four days with her initial foster, she was transferred to FTB, where she remained for over four years, until September 15, 2024. During her time at FTB, her veterinary costs totaled $62,247.

Evie was purchased as a baby from Napa feather Farm in 2014. Her surrenderer described Evie as a very sweet and loving companion, whom she cared for deeply. However, she recognized that her current circumstances were not ideal for providing Evie with the attention and care she deserved. She was pregnant with her second child and, with a demanding full-time job and a two-year-old toddler, she already struggled to dedicate sufficient time to the bird.

She believed Evie would thrive as the sole companion of an older individual or couple who could spoil and love her unconditionally. While the bird might do well in a multi-bird household, the surrenderer emphasized the importance of ensuring she received adequate attention. Evie enjoyed being part of daily activities, spending time out of her cage, sampling fruits and vegetables and, of course, making a mess.

The surrenderer also raised concerns about the bird’s emerging hormonal behaviors, which might require additional care and attention as they progressed—care she feared she would not be able to provide. While she admitted she would love to keep the bird, she felt strongly that Evie deserved a better situation.

Almost immediately upon arrival, Evie was given Lupron—FTB’s standard treatment for plucking. According to Dr. Van Sant, Evie remained in a perpetual hormonal state. She claimed that when Evie was moved to another cage temporarily for cleaning, she crawled into her food dish and immediately exhibited nesting behaviors. Evie was placed on a strict meal-feeding regimen and housed in a cage with no chewable or shreddable materials, no cup holders and no bells, based on Dr. Van Sant’s theory that such items stimulate nesting—an approach FTB commonly uses, but which contradicts the individualized needs of pet birds. Internal emails from 2020 show Dr. Van Sant labeled Evie as “permanently damaged,” a candidate for long-term care due to “hormonal deterioration” and a supposed severe endocrine disorder.

Despite multiple rounds of Lupron, deslorelin implants, blood panels and radiographs, no definitive diagnosis was reached. Evie was moved to an outdoor aviary in early 2021 but returned after having a seizure. Robenacoxib injections were tried in lieu of ABV testing but were later discontinued for lack of effect. By the time she left FTB in September 2024, Evie had destroyed nearly all of her feathers.

When she first arrived at her foster home, she would quickly eat everything in her dish. Over time she came to understand that food would be available to her throughout the day, and this habit diminished. She was adopted a month later, and as of April 2025, she has shown no signs of seizures or temperature sensitivity. She now has access to bells, chewable toys and foraging opportunities and is no longer meal-fed. Although she may never stop plucking entirely, the behavior has significantly decreased, and she is thriving.

An important aspect of the apparent successful case outcome appears to largely include Evie’s departure from the care and treatments and FTB, and moving away from labeled constructs with a more targeted approach to the issues at hand.

Evie, May 2025

Max

Max came to Mickaboo in September 2017 after being surrendered by his previous family. He was a beloved companion but they felt he would be happier in a more suitable environment, citing signs of stress due to the presence of other African greys in their household. Entrusting Mickaboo with his care, they hoped to provide Max with a better life.

Unfortunately, Max’s journey proved challenging. His first adoption placed him with an inexperienced individual unfamiliar with African Greys, resulting in aggressive behavior and his return. Over several months, Max was moved between multiple foster homes, none of which successfully addressed his needs. Labeled as irrevocably aggressive, he was transferred to FTB and subsequently passed to another rescue organization, which later ceased operations. Max returned to FTB on September 16, 2019, where he remained until July 27, 2024.

In July 2024, Mickaboo found a foster willing to take Max, despite warnings from FTB and Mickaboo leadership about his history of significant aggression. Described as unpredictable and quick to lunge, FTB claimed Max required a high level of caution during handling. He was only let out of his cage for routine examinations, which were conducted using a towel in the dark. The foster was asked to sign a waiver acknowledging these challenges.

Max’s case underscores a critical gap in Mickaboo’s approach to handling “problem” birds. Once labeled aggressive, Max was sent to FTB and largely forgotten, despite the fact that behaviors like biting can often be mitigated with proper intervention and care. Fortunately, Max’s story has taken a positive turn. His foster has since officially adopted him, reporting that Max has shown no signs of aggression, including biting. He has transformed into a gentle and affectionate companion who enjoys scritches and interaction, demonstrating the impact of a patient and understanding home.

An important aspect of this successful case outcome one again appears to largely include Max’s departure from the care and treatments at FTB, and moving away from labeled constructs of what Max is, towards a more focused interventional strategy.

Gizmo

Gizmo is a ~20-year-old Blue and Gold macaw who was surrendered in June 2022 along with another macaw, Tim. They had been well cared for until their elderly guardian became ill, and a neighbor stepped in. During this time, Gizmo and Tim began fighting—Gizmo’s beak was injured and developed a serious infection, and he began feather-picking. The bonded pair was separated: Tim went to a boarding facility and was eventually adopted; Gizmo was sent to FTB, where he remained under Dr. Van Sant’s care until March 2024.

Upon his arrival at FTB, he received Lupron, a deslorelin implant and a battery of tests. He was placed on the standard FTB diet—Lafeber’s Nutri-an Foraging and Weight Maintenance 12 oz cakes, Harrison’s Lifetime Coarse, fruits and vegetables—and put on a meal-feeding routine. His treatment included Red LED Light Laser Therapy, which Dr. Van Sant said was aiding the healing of his beak lesion. During his stay at FTB, Gizmo incurred $33,193 in vet costs.

On January 3, 2024, Sarah noted on Slack that no updates were being provided for birds at FTB. Efforts to move Gizmo had been blocked due to reports of a raw internal beak wound. On January 19, a foster was identified, but Gizmo wasn’t transferred until March 23 due to difficulties removing him from FTB.

On July 9, 2024, Gizmo’s foster brought him to MCFB for a beak infection follow-up. Due to lack of prior imaging, x-rays were taken, revealing deep infection. The doctor found decayed tissue and fluid, which tested positive for E. coli. Dr. Speer cleaned and reshaped the beak to encourage proper keratin growth and prevent recurrence.

Gizmo stayed at MCFB until that Friday and was sent home with silver sulfadiazine. Dr. Speer was optimistic that the infection wouldn’t return now that the overgrowth was removed. Gizmo’s surgery at MCFB cost $1250. We have records of one follow up visit in August 2024 for a recheck and further beak shaping, which was $163. Even with regular follow up visits to trim the beak, this amount remains far lower than the amount charged by FTB.

A July 1, 2024 update from his foster reported that Gizmo was cheerful and eating well. Efforts to slow his feeding using foraging toys are ongoing. His habit of overeating—gobbling all his food at once and spending the day digesting—was likely caused by the meal-feeding routine used at FTB. Dr. Speer agreed that this pattern may have contributed to digestive issues and retained droppings noted in 2022. The foster is gradually introducing more complex feeders to encourage slower, more natural eating behavior.

As of April 2025, Gizmo is doing exceptionally well. He is no longer receiving hormone implants and, notably, has had no recurrence of the issues Dr. Van Sant previously attributed to hormones. His beak continues to improve—while the growth has been slow, it no longer appears to be infected. He visits Dr. Speer periodically for shaping to support healthy regrowth. Gizmo’s foster reports that he is a gentle, quiet and affectionate bird who enjoys sitting calmly on his foster’s arm while she works, often resting his head on her shoulder. He has truly become a sweet and steady companion.

Lilly

Lilly is an African grey surrendered by the daughter-in-law of Lilly’s owner when the owner died after a long illness. The woman’s son was unable to continue caring for her. Lilly had spent her life with an older woman who doted on her. Before her human got sick, Lilly spent a lot of time out of her cage and was at one point an accomplished flier. But when her human got sick and could no longer care for her, she began picking and barbering her feathers. She has laid eggs in the past.

Upon intake on 2/27/21, she was sent to FTB and remained there until she was fostered out on 7/15/24. In those 3.5 years, $45,958 in costs were accrued. Her treatment is similar to Evie’s, with the same success. She was returned to FTB for severe feather barbering in early 2025. It is unknown whether her foster had been following FTB’s “cure” for feather picking, but the foster said in an email that Dr. Van Sant thinks Lilly “is maybe too happy and has increased her feathers plucking. Fern thought it might be a good idea for her to go back for a week or 2 to get her on the right track with Lupron injections.” She was finally discharged two months later. She has now accrued $49,000 in costs.

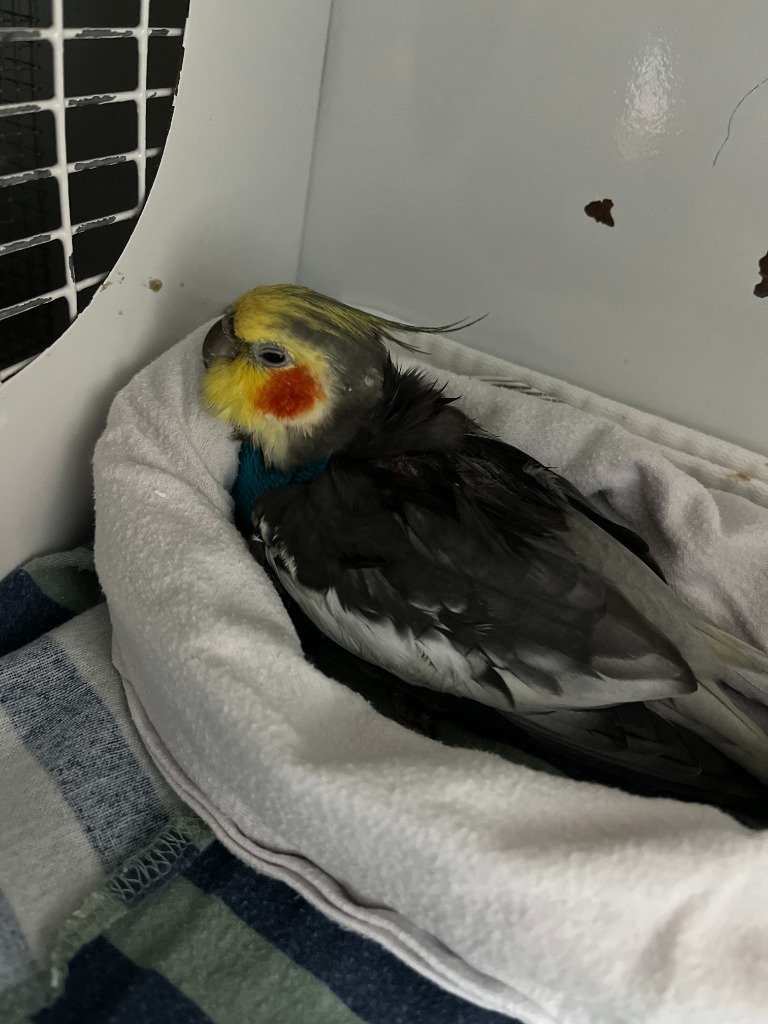

Sara

Sara, a cockatiel, was brought in as an injured stray on January 30, 2023 and taken to the Bay Area Bird Hospital (BABH). After being discharged on February 3, 2023, she went into Tammy’s care. Tammy reported that Sara had “crackly lungs” and pain from her injuries. She arranged for further treatment at FTB, where Sara arrived on February 7, 2023. At FTB, she received Lupron and underwent extensive testing, including direct fecal tests, gram stains, imaging with a barium study, standing film, ultrasound and multiple abdominocentesis throughout February. Additionally, she received Lupron twice more, along with a Dex SP injection.

In March, Sara underwent further imaging and received three more Lupron injections. On March 31, 2023, she was released into Tammy’s care. Tammy reported that Sara was “fat and happy,” and there was no fluid buildup in her abdomen. However, Sara had gained excess weight, which Tammy decided required meal feeding and restricted access to treats. FVS suggested the fluid buildup might have been due to a reproductive cyst, indicating the need to monitor her hormone levels closely.

After a week with Tammy, Sara returned to FTB on April 8, 2023, due to heavier breathing, abdominal changes and rapid weight gain. FVS suspected the issue to be reproductive activity rather than fluid buildup, and Sara was kept for hormone treatment and weight management to ensure her condition was stable. Between April and the end of July, Sara received further imaging, a deslorelin implant, enrofloxacin treatments, fluid analysis, multiple gram stains, Metacam injections, Lupron injections and other hospital treatments.

By the end of July 2023, Sara had been deemed a special needs bird. Due to her history of fluid buildup in her abdomen, FVS says she requires ongoing observation and timely treatment. She was released to a vet tech who works at FTB and who has taken home other Mickaboo birds. In August 2023, she underwent additional testing, including fecal analysis, gram stain and a Lupron injection.

Sara did not require further veterinary visits until December 2023, when tests were conducted for changes in her fecal color and consistency. Beginning in February 2024, her testing and treatments resumed on a monthly basis, similar to the treatments she received earlier.

In the two years since entering Mickaboo’s care, Sara has accrued $20,000 in veterinary expenses.

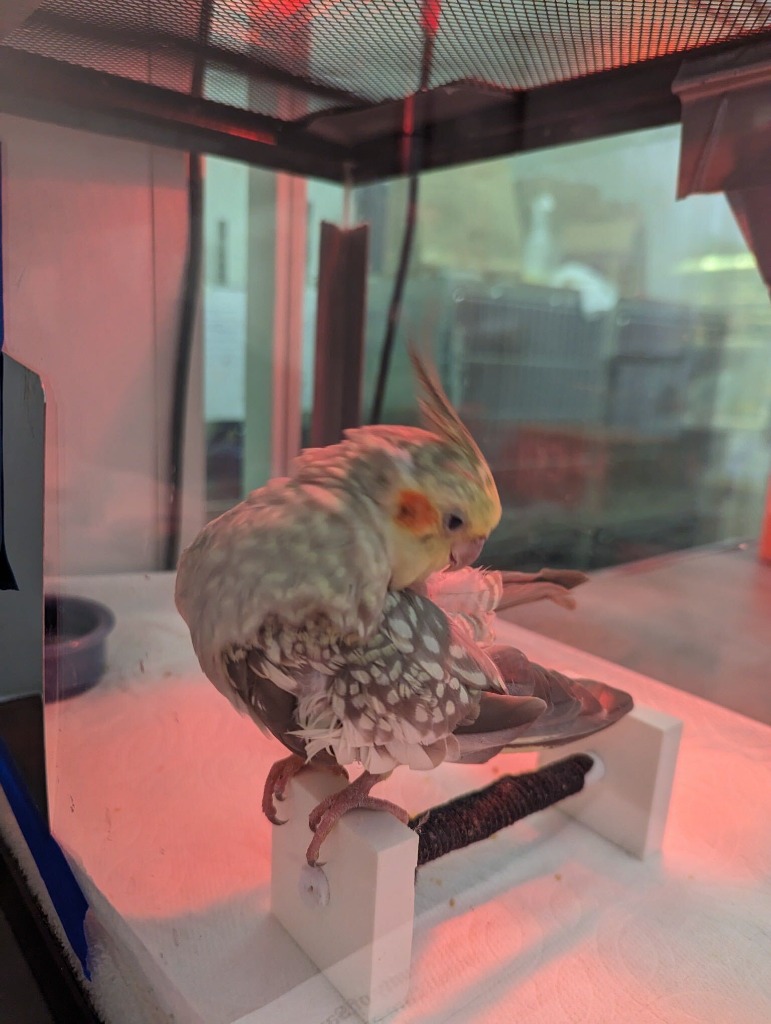

Kol

Kol, a twenty-two-year-old cockatiel, was surrendered on November 29, 2023, by a Wildwood client who was seeking euthanasia rather than conducting further diagnostic tests for Kol’s enlarged crop. He was initially hospitalized at Wildwood until December 3, 2023, when he was transferred to FTB. Upon arrival at FTB, Dr. VS removed a significant amount of old food from Kol’s crop, fitted him with a crop bra and administered fluids with Valium.

During Kol’s stay at FTB, he underwent various tests and treatments, including imaging, culture/sensitivity IN, gram stain with culture, Wright’s cytology and direct fecal examination. He was also given seven days of gavage feeding and a Robenacoxib injection.

An update on January 8, 2024 indicated that Kol was experiencing another backup of food in his crop. He had been given NutriAn cakes, but it was later realized that he could not properly digest the particulates. Since then, Kol has remained hospitalized at FTB, receiving regular care, including frequent Robenacoxib injections, occasional gavage feedings and additional tests, such as several direct fecals and Spironucleus PCR probes, which returned positive results. He was also administered a PBFD/APV/Chlamydia combination treatment for trial purposes.

Costs: In the sixteen months since December 2023, Kol’s veterinary care costs have totaled $26,052.

Betty

Betty, a budgie, came into Mickaboo’s care in late March 2022 with another budgie, Buddy. On arrival, Betty was severely underweight. The birds were fostered without proper documentation in Mickaboo’s system, and in early April 2022, the foster took them to Dr. Susan Ford, a vet not typically used by Mickaboo. Without Mickaboo’s knowledge, both birds were treated for a month with antibiotics, antifungals, anti-inflammatories and ivermectin.

On May 4, 2022, Betty returned to Dr. Ford for respiratory issues. Dr. Ford noted Buddy had mites, suggesting Betty was also infested. She diagnosed Betty with serious lung issues, possibly from aspiration or mites, and recommended euthanasia. However, Dr. Ford later suggested the aspiration may have been caused by the foster attempting to syringe water. Betty was kept overnight with Buddy and given gavage feeding, fluids and injectable antibiotics.

The birds were then transferred to MCFB, where they were hospitalized for a month. No outcome was recorded for Betty. At the end of June 2022, Dr. Speer reported both birds were clear but advised waiting for two more tests before adoption. On September 6, 2022, the foster said both birds had been cleared.

There was no further communication about Betty until March 3, 2023, when the foster reported Betty was not putting weight on one foot and had lost 6 grams. At MCFB, it was suspected she had a mass affecting her nerves. Tammy believed it was either a soft tissue injury or a gonadal mass and recommended managing her with Lupron and meloxicam. She advised against further diagnostics to avoid stress. On March 5, 2023, the doctor reported Betty was comfortable and stable but not showing immediate improvement. On March 9, Tammy learned Lupron had not been administered for what she believed was a reproductive tumor.

Betty was discharged on March 13, 2023, with tamoxifen. The doctor suggested follow-up and possible future diagnostics depending on her response. However, Tammy remained committed to Lupron, and Betty was transferred to FTB, where she was hospitalized and tested extensively from early April to mid-June—69 days in total.

On May 3, 2023, Tammy reported Betty’s uric acid was high and expressed concern about gout. By June 15, it was still elevated. Betty was sent home with Michelle Y. at Fern’s request, who said Betty was not responding to treatment and asked Michelle to try her usual method—housing birds in cages that encourage movement.

Betty was hospitalized again on September 1, 2023, and died the next day. A necropsy was performed but no results were recorded. Death notes listed “high uric acid, gout, ovarian cyst” and the cause as “unknown.” Total FTB costs were $7,206 and MCFB costs were $1,618.

Angel (Cockatiel)

Angel, a female cockatiel, came to Mickaboo on April 23, 2023. On June 2, 2023, she was seen at MCFB for persistent polyuria and sneezing and was diagnosed with Spironucleus via fecal swab. She was started on Metronidazole. For reasons unknown, her care was transferred to FTB on June 6th, and a PCR test was ordered. Spironucleus was confirmed via UGA, and Tammy and Dr. Van Sant insisted on switching Angel to Ronidazole, stating Metronidazole was ineffective. A June 28 PCR test came back negative, though her polyuria returned soon after.

Angel was adopted by Colleen Shaw on August 13, 2023. In early September, she suffered a seizure and began exhibiting unusual droppings—retaining stool overnight, then passing large, malodorous feces in the morning followed by polyuria throughout the day. On December 15, she became acutely ill and was taken to North Pen Emergency Clinic. While she improved by December 18, no diagnosis was made. Tentative explanations included heart disease or heavy metal toxicity, though the latter was unlikely based on her environment.

On January 22, 2024, Angel experienced another syncope episode and was prescribed Sildenafil, which stabilized her. On March 15, she tested positive for Spironucleus again—likely transmitted from Colleen’s other bird, Charlie. After another stay at FTB, where she received weekly Robenacoxib injections, Angel was sent home on March 31. Within days, she experienced two more seizures. PDD was suspected, and despite being placed on Diazepam, the seizures continued. She was returned to North Pen for further evaluation.

On May 20, 2024, Colleen surrendered Angel due to her ongoing health complications. She was designated a permanent foster. In September, updates indicated she was stable, though she had a seizure and continued to struggle with bowel issues. She also broke two tail feathers, which were pulled. On September 14, Tammy acknowledged that Angel’s diagnosis remained unclear and PDD had not been ruled out. From September 19, Angel was hospitalized at FTB for four days, with costs covered by Mickaboo.

Angel’s case reflects a pattern of extensive but inconclusive treatment at FTB under Dr. Van Sant. Despite repeated hospitalizations and interventions, her condition remains undiagnosed. She is now a permanent foster, still dealing with seizures, polyuria and suspected PDD. She has bonded with Charlie and is more comfortable in her home environment. Notably, Mickaboo now also covers Charlie’s medical costs, despite him never being a Mickaboo bird. In just under two years, Angel’s care has totaled $14,000 in veterinary expenses. Charlie’s expenses remain untracked.

Guido

Guido, a green cheek conure, was surrendered to Mickaboo on May 16, 2024, after being sick for several months at a Petco store, where she had been kept in the back due to her condition. Despite antibiotic treatment since February, her nasal discharge persisted. Initial infections—Pseudomonas and gram-positive cocci—were cleared, but clear ropey mucus, mainly from the right nare, continued. X-rays showed no abnormalities, raising suspicion of a foreign body, possibly from prior housing on paper pellets. Symptoms briefly improved with corticosteroids but returned when tapered.

Upon intake, Guido was taken directly to FTB, where she received Vitamin ADE, Metacam, a nasal flush and, on May 18, gavage feeding, another flush and unspecified oral and topical treatments. FTB conducted extensive diagnostics, including direct fecal testing, DNA microbiome analysis, bile acids panel, gram stain, culture/sensitivity testing and Wright’s cytology.

Early lab results showed gram-positive overgrowth and a fruity odor suggestive of Pseudomonas. A culture later confirmed Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, both resistant to many antibiotics but susceptible to ceftazidime, gentamicin, enrofloxacin and others. Bloodwork showed a mildly elevated white cell count and a slight left shift, suggesting low-grade infection or stress. Other values were normal.

Throughout June, Guido underwent additional gram stains, recheck cultures and imaging. In early July, she received nebulization therapy and had a radiology consult. Imaging revealed chronic nasal and infraorbital sinus disease, while other systems appeared normal. A CT scan of the skull and lungs was recommended but not completed. Between July and September, she received daily unspecified treatments and underwent nine more gram stains.

In the first FTB records, Guido is referred to as “Mango,” her intake name. Later invoices list her as “Maggie.” As of late September, it appears she was sent home—without Mickaboo’s knowledge—with Corrina Chinn, daughter of Michelle Yesney and FTB’s receptionist. This type of informal transfer is not uncommon at FTB. Guido continues treatment there; her last boarding charge included cephalexin suspension and voriconazole. On October 16, 2024, she had a recheck exam, gram stain and was again given cephalexin.

Despite months of intensive and often nonspecific treatment at FTB, as far as we can tell, Guido’s condition remains unresolved. As of April 2025, her veterinary costs total nearly $15,000.

Rosco

Rosco, a red-lored Amazon, came to Mickaboo in May 2019 after his guardians could no longer afford veterinary care. At intake, he was seen at MCFB, where a biopsy confirmed squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. He was treated with ciprofloxacin, Metacam, tramadol and fluconazole. MCFB also corrected a beak malocclusion.

In June 2019, the tongue lesion recurred significantly, and for reasons that remain unclear, Rosco was transferred to FTB. There, the lesion was treated with CO2 laser ablation in June, July, August and December, alongside culture-guided antibiotics. His beak was trimmed regularly, and the foster provided daily saline irrigation and follow-up care.

The lesion was lasered again in 2020 and 2021 and twice in 2022. Additional treatments for recurrences occurred in February, May and August 2023. In October 2023, Rosco was moved to a new foster. In December, the lesion was manually debrided, and another laser ablation was scheduled for January 11, 2024. His beak was trimmed again for malocclusion.

Mickaboo required Rosco to remain with a foster willing to take him exclusively to FTB for treatments every four to six weeks. The foster was also instructed to mist his mouth several times a day with saline solution from FTB, as Rosco couldn’t fully close his beak and his tongue would dry out.

On January 11, 2024, Rosco was anesthetized at FTB for CO2 laser resurfacing of his tongue. A MIDOG was submitted to assess the extent of secondary and possible fungal infection, and he was placed on parenteral antibiotics while awaiting results.

Rosco was released back to his foster on January 24, 2024, appearing stable. He died the following day. A necropsy was reportedly performed, but no results were shared. In Mickaboo’s system, his cause of death is listed as “unknown.” His care at FTB amounted to $21,000.

Gus

Gus,5View the PDF

More about Gus’s Treatments a 43-year-old yellow-naped Amazon, was surrendered to Mickaboo on June 24, 2019, after his family of 38 years relocated. He has a complex medical history involving multiple vets, including Wildwood, MCFB, an avian eye specialist and Dr. Renee Luehman. His care was inexplicably transferred to FTB on April 10, 2024. To date, Gus has incurred $18,300 in vet costs—$11,000 with prior clinics over six years, and $7,500 at FTB in just ten months.

Gus was diagnosed with advanced atherosclerosis in 2019 after losing his vision suddenly. While mature cataracts explained some vision loss, the rapid onset raised concerns about stroke or central blindness. Imaging confirmed arterial calcification, especially in areas affecting his limbs. He was also suspected to have hypertension, possible liver involvement, and neurologic deficits. Treatments included enalapril, isoxsuprine, meloxicam, tramadol, and gabapentin. Vets emphasized the importance of quality of life, minimal handling and gentle home support.

His foster frequently reported vague or fluctuating symptoms—unexplained behavior changes, weight shifts, and gastrointestinal irregularities—prompting repeated exams, medication adjustments, and emergency visits. These patterns raised concerns of caregiver-induced overmedicalization, prompting some to question whether Munchausen’s by proxy could be a factor.

Between April and June 2024, Gus was hospitalized at FTB for 31 days and subjected to extensive diagnostics and frequent, often nonspecific treatments. These included nine exams, two bile acid panels, two T4s, cholesterol screening, repeated gram stains, PCV/TPs, saline misting, injectable hydration, Robenacoxib injections, oral and topical meds, laser therapy, and an unspecified surgery.

At FTB, in just two months, he received more interventions than in some previous years—raising cost, stress and concern about oversight. Gus now becomes part of our ongoing 24-month study tracking treatment outcomes and spending patterns at FTB.

Tequila

Tequila, an Amazon parrot, has been subjected to unusually frequent beak trims and extended periods of medical boarding. These trims often require four days of boarding, and as of April 2025, the associated costs have reached $13,500. This approach raises serious concerns about its sustainability and appropriateness for Tequila’s long-term well-being.

Tequila, a red-lored Amazon, came to Mickaboo in February 2022 after his guardian passed away. When a volunteer conducted a welfare check shortly after, he found Tequila living in poor conditions, with a foot-high accumulation of feces in his cage and signs of a scissor beak requiring immediate medical attention. Tequila went to MCFB, where he was diagnosed with a beak malocclusion, dangerously long nails, bald spots and possible atherosclerosis. Diagnostic tests and x-rays were performed, and treatment was initiated for both fungal and bacterial infections. Despite age-related cardiovascular findings, his prognosis was good, and a slow dietary conversion was recommended.

Tequila moved to a new foster home in August 2022, at which time, he was taken to For the Birds (FTB) for a beak trim. This led to complications—Tequila struggled to eat and required monitoring and assistance. Over the next two years, Tequila returned to FTB nearly every month—and sometimes twice a month—for regular scissor beak trims. Each visit was often followed by reports of difficulty eating, lethargy, or changes in droppings, resulting in additional check-ups, gram stains, and occasionally weekend boarding.

The frequency of visits remain high, with FTB often suggesting continued observation, rechecks, or adjustments in treatment, such as antifungals or reshaping the beak. In September 2024, Sarah questioned why Tequila was being boarded at FTB, particularly for routine beak trims. His foster claimed he wasn’t boarding him, yet FTB invoices reflect monthly boarding charges coinciding with beak care.

Tequila’s case highlights a broader issue with the current approach to managing chronic conditions in long-term foster cases. Prolonged and repeated medical boarding not only places significant financial strain on resources but also raises questions about its impact on the bird’s quality of life. A more sustainable and bird-focused strategy must be considered, emphasizing preventative care and minimizing the need for frequent invasive treatments.

It is essential to evaluate whether this ongoing approach truly serves Tequila’s best interests or if adjustments can be made to provide him with a more stable and supportive care plan moving forward. His case underscores the need for a more efficient and compassionate strategy in managing chronic medical needs.